5.3 The Studio Assets

For what was evidently a highly prolific (and presumably necessarily highly organised) studio, surprisingly little archival material survives. Nonetheless, it is possible to glean some information about the studio assets from the few known written sources.1 After the death of Van de Velde the Younger in 1707, the studio continued to produce paintings under the leadership of the Younger’s son Cornelis van de Velde (1674-1714), whose signed work attests to his continuation of the family legacy.2 As Daalder notes, an advertisement for a studio sale in August 1713 indicates that Cornelis had begun to wind up the London studio the year before his death in 1714.3 The inventory of his estate, signed by his widow Bernarda van de Velde, gives a cursory picture of some items that might have been in the Van de Velde studio, including: 'Fifteen pictures, twenty unfinished cloths for pictures, ten books with paper drawings, […] one chest of drawers, four flags belonging to a boat …'.4

It is worth noting that there is no such inventory for Van de Velde the Elder or Van de Velde the Younger, because the family studio continued to operate after the death of both men.5 It is thus tempting to interpret these items as remnants inherited at least in part from the studio of Cornelis’s father and grandfather.6 Brief as it is, the probate inventory is therefore useful in reconstructing the possible appearance of the Van de Veldes’ studio, with finished pictures, unfinished canvases and volumes containing drawings.

The physical evidence of the Van de Veldes’ extant paintings and drawings themselves can illuminate the written descriptions further. For example, in examining the evidence of canvas dimensions in the Greenwich collection, Kendall Francis observed that the Van de Veldes seem to have worked on canvases that were purchased stretched, conforming to canvas sizes identified by Jacob Simon in his study of British portrait painters and their canvas sizes.7 We might also note that on some occasions, Van de Velde the Elder seems to have been responsible for acquiring frames for his pictures and undertaking the framing himself. On 8 October 1688 (OS), he wrote to Lord Dartmouth that 'I brought laste Fryday at my Lords house ye ffive pieces of pictures, as are knowne to my Lord, and these day being Moonday, I have put them in theire golden frames, which are extraordinary curious & precious. Which I did in the presence of my Lord’s brother, to whom it is knowne'.8

Similarly, the sheer size of the surviving Van de Velde drawings corpus suggests ample material to fill more than 10 volumes.9 Meanwhile, a survey of the almost 1,500 Van de Velde drawings in the Greenwich collection undertaken in preparation for the exhibition and the associated Getty Paper Project initiative revealed very few signs of drawings having been bound or pasted down. It seems likely therefore that the ‘books with paper drawings’ were bound volumes of blank pages interleaved with loose drawings, as was often the case among Dutch drawings collectors of the period,10 and as can be seen in Van Musscher’s portrait of a painter formerly identified as Willem van de Velde the Younger [12].11 Unbound drawings were vital to the Van de Veldes’ creative process, especially to the mix-and-match approach to building compositions and their extensive use of offsets (counterproofs), a practice dependent on loose leaf drawings. Storing drawings unbound also facilitated the regular reorganization that an ever-growing drawings collection required, as well as exchange, perhaps loan, of drawings with/to other artists.

In addition to the more standard objects of an artist’s studio, the Van de Velde studio is said to have contained a ship model, which, alongside the ‘four flags belonging to a ship’ in Cornelis’ probate inventory, represents perhaps a marine painter’s answer to the theatrical props and statuettes commonly found in a history painter’s studio [13].12 At the beginning of the 18th century, Baynbrigg Buckeridge described in his Essay towards an English school of painters the important role of a ship model in the Van de Velde studio: 'For his better information in this way of Painting, [Van de Velde the Elder] had a Model of the masts and tackle of a Ship always before him, to that nicety and exactness, that nothing was wanting in it, nor nothing unproportionable. This model is still in the hands of his son'.13

12

Michiel van Musscher

Portrait of a man previously called Willem van de Velde II (1633-1707)

Vienna, private collection Liechtenstein - The Princely Collections, inv./cat.nr. GE 2397

13

Installation view of The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea, Van de Velde Studio, The Queen’s House

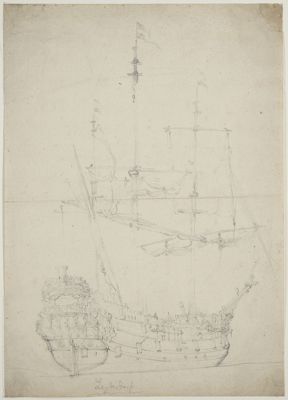

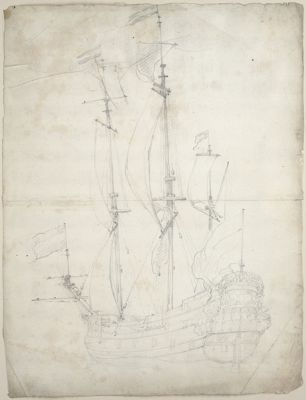

Assessing Buckeridge’s description while preparing the exhibition, we came to the conclusion that access to a ship model would have been particularly advantageous in the production of shipwreck and storm paintings, which could be used in conjunction with rapid compositional sketches and ship portraits to piece together a painting. This ship model would not need to be – and is unlikely to have been – an elaborate object made in the Navy Board style for elite collectors detailing the specific decoration of a prized vessel.14 After all, the Van de Veldes had a wealth of highly detailed ship portraits drawn from life, which could be used to inform the depiction of the detailed carving of individual vessels in different compositions. Rather, the rigging of a three-masted ship is more or less the same regardless of the ship’s rate and so a simplified model with a standard rig had the advantage of being able to stand in for multiple individual vessels, enabling the Van de Veldes to explore different sail arrangements in order to ‘place’ a ship within a given composition relative to the imagined weather conditions. We can see this at work in offsets (counterproofs): a comparison of two offsets showing the Dutch ship Leiderdorp – the first transferred from an original drawing of the hull and the second transferred in turn from the first offset [14-15] shows how this process of replication enabled the artist to quickly reproduce the contours and intricate details of a given ship’s hull and then experiment freehand with the sails and rigging.

14

Willem van de Velde (II)

Portrait of the "Leiderdorp", 1667 (?)

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. PAH1793

15

Willem van de Velde (II)

Portrasit of the "Leiderdorp", 1667 (?)

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. PAH1794

Where the ship model conceivably came into its own, however, was in the production of storm and shipwreck scenes, a genre that enjoyed increasing popularity in England around the end of the 17th century.15 Although the Van de Veldes would have experienced storms and other dangerous situations at sea, drawing from life in these circumstances was challenging and it comes as no surprise that there are no existing drawings of such situations of the same detail as those created of battles and royal events. There are many rapid compositional sketches of ships in perilous situations, some of which might have been memories of situations witnessed first-hand, but even if that was the case, there remained still a significant gap between such a sketch and a highly finished painting. A ship model robust enough to withstand regular handling – and perhaps propping up at different angles to simulate heavy seas – would have helped bridge this gap between imagination or memory and the canvas.16

Notes

1 Daalder 2016, p. 182-85.

2 One such work (Royal Museums Greenwich, BHC0985) was included on an easel as part of the studio evocation in the exhibition.

3 The advertisement in the Daily Courant, 20 August 1713, notified readers that ‘A small Parcel of Original Pictures remaining of Mr. Cornelius Vande Velde’s, will begin to be Sold to Morrow August the 21st, at his Lodgings the 2 Black Posts in King-street, Bloomsbury’. Daalder 2016, p. 183-84.

4 Probate inventory of Cornelis van de Velde, 6 November 1714 (OS), Kew, National Archives, PROB 4/22810. Published in Daalder 2016, appendix 5, p. 197.

5 Daalder estimates that the Van de Velde studio operated for some 70 years across the three generations of leadership. On the studio’s legacy: Daalder 2016, p. 182-85.

6 There had been a studio sale following the death of Van de Velde the Elder, on 24 January 1694, but the catalogue for this is untraced. The sale was advertised in the London Gazette, 16 January 1694. Daalder 2016, p. 176-7 and Karst 2013-2014, p. 28.

7 Francis made a study of seven canvases in the collection at Greenwich, six of which fit the dimensions listed by Simon as kit-cat (91.5 x 71.1 cm), small half-length (118 x 86.4 cm) and half-length dimensions (101.6 x 127 cm). Francis 2020, p. 15 and Simon 2013.

8 It is worth noting that this framing did not take place at the Van de Velde studio but rather at the home of the collector. Letter from Willem van de Velde the Elder to Lord Dartmouth, 8 October 1688 (OS). Staffordshire Record Office, Stafford, Papers of The Legge Family, Earls of Dartmouth D(W) 1778/Ii/1370. Published in Daalder 2016, appendix 4, p. 196.

9 An average album probably had capacity for more than 100 drawings. Kleinert 2006, p. 68, citing the exhibition catalogue Rembrandts schatkamer Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam, 1999-2000, p. 25. The practice of keeping drawings in bound volumes was itself an indication of a certain financial standing (as well as of the value ascribed to the drawings contained in them) as such volumes were expensive items, costing up to 10 Dutch guilders each. Kleinert 2006, p. 69, citing the exhibition catalogue De prentschat van Michiel Hinloopen, Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam 1988, p. 18.

10 Kleinert 2006, p. 68.

11 Kleinert 2006, p. 141. Van Musscher’s subject was identified as Van de Velde the Younger from as early as 1835, when the painting was reproduced as the frontispiece to volume 6 of John Smith’s Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters. More recently this has been disputed. For example, Van der Merwe suggests Adriaen van de Velde as an alternative identity for the sitter. Van der Merwe 2017, p. 66.

12 Later marine painters who considered themselves as heirs to the Van de Veldes’ practice, such as Nicholas Pocock (1740/41-1821) and Edward William Cooke (1811-80), also kept ship models in their studios.

13 Buckeridge 1706, p. 473.

14 Stephens/Ball 2018.

15 It is worth noting that the Van de Veldes’ salaries were a retainer, not a promise to work exclusively for the Stuarts. Daalder 2016, p. 145. Especially if the payment of their royal stipend was unreliable (see above), commissions for the open market would have been a given.

16 It is as a result of these conversations that we commissioned from model maker Kelvin Thatcher, with the help of curator Simon Stephens, a simple ship model with standard rig for the exhibition’s reconstruction of the Van de Velde Studio. For further discussion of the Van de Veldes’ relationship with ship models: Stephens/Ball 2018, particularly p. 49-50.