4.2 Portraits for the Kentish Gentry

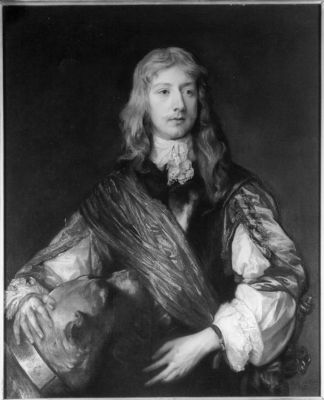

Van Hoogstraten’s English portraits have a new sense of elegance and refinement. His portrait of Thomas Godfrey (1640-1690) [6] is one of two dated 1663.1 They are a departure from the more conventional, restrained portraits he painted in Dordrecht [7], and show that the artist was looking at new models of emulation that would fit better with the expectations of potential English clients. Not surprisingly, Van Dyck’s modish portraits of English courtiers with hounds [8] played a significant part in Van Hoogstraten’s conception of Godfrey, alluding both to loyalty and the aristocratic sport of hunting, and ultimately harking back to Titian’s portrait of Charles V (1500-1558) from 1533 (Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado). Another possible source is Lely’s portrait of Sir Ralph Bankes (c. 1631-1677) (c.1660; New Haven, Yale Center for British Art), probably one of Van Hoogstraten’s English patrons, where the three-quarter-length sitter is also seated and has a raised and dangling left arm, but the dog is more distant.

Godfrey was the member of a prominent Kentish landowning family that had been established at Lydd on Romney Marsh for generations.2 He was a cousin of the magistrate Edmund Berry Godfrey (1621-1678), whose murder in 1678 was a key-moment in the so-called ‘Popish Plot’.3 In July 1658 Thomas Godfrey matriculated at New College, Oxford, but never took up his place at the university, possibly because of strained financial circumstances.4 As the son of a second son, his position would have been precarious. However, his circumstances improved greatly in 1663, the year that the portrait was painted, when he married a wealthy heiress, Mary Toke (1640-1698), the widow of Sir Robert Moyle (1636-1661), and the daughter of Nicholas Toke (1588-1680). Subsequently, he moved into the home of his new wife, Buckwell in the parish of Boughton Aluph, north of Ashford.5 These marriage alliances among a small number of gentry families were also extremely important in Kent, where blood and kinship mattered almost more than in any other county.6 Given its proximity to both London and the continent, and the wealth of its agricultural land, Kent was a surprisingly sophisticated market for portrait painting and other cultural pursuits, and Thomas Godfrey was obviously keen to secure the services of a Dutch artist, newly arrived from the Netherlands.7

Some years later, in 1667, Samuel van Hoogstraten painted two portraits of the brothers, Sir Norton (1601-1685) [9] and Thomas Knatchbull (d.1703) [10]. They belonged to the same network as Thomas Godfrey and were related to him through marriage.8 Sir Norton’s background shows many of the characteristics of the Kentish gentry: inheritance of a landed estate (Mersham Hatch near Ashford), education at a university (Cambridge) and one of the London inns of court (Middle Temple), and service to the county as a Justice of the Peace and MP.9 However, he was different from many of them in that he was a deeply learned individual, with extensive intellectual interests, which must have endeared him to the polymath Van Hoogstraten. He was a distinguished theologian and had published a highly regarded Latin commentary on the New Testament in 1659 that ran into several editions and was reprinted at Amsterdam and Frankfurt.10 The diarist John Evelyn heard him preach in the chapel of a neighbouring property in 1663 and referred to him as a ‘worthy person and learned critic, especially in Greek and Hebrew’.11 The sale catalogue of his library, which survives, reveals that his book ownership was much more diverse than that of his contemporaries, and apart from theology and classical literature, there were texts on philosophy, poetry, medicine, geography, and history, in a range of languages (Latin, Hebrew, French, Italian and English).12

6

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Portrait of Thomas Godfrey of Burton Aleph (?-1690), dated 1663

Sale London (Christie's) 1989-11-17, no. 44

7

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Portrait of Jacob Ouzeel (1601-1666), dated 1661

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum, inv./cat.nr. DM/936/513

8

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Thomas Killigrew (1612-1683), 1635-1638

Weston Park (Weston-under-Lizard), The Weston Park Foundation

9

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Portrait of Sir Norton Knatchbull, 1st Baronet (1602-1685), dated 1667

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum, inv./cat.nr. DM/021/1451

10

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Portrait of Thomas Knatchbull Esq., 1662-1667

Whereabouts unknown

We know much less about his younger brother Thomas, who was Recorder of Maidstone. He stabled his horses and possibly received his meals at Mersham Hatch, paying £60 per year for the privilege.13 In his last will and testament of June 1682, Sir Norton referred to him as his ‘good brother’ and bequeathed him ‘one hundred pounds as a token of [his] love’.14 Why Sir Norton chose to have his brother, rather than his wife Dorthea Honywood (d.1694), portrayed by Van Hoogstraten, is far from clear. She was subsequently portrayed by a much more mediocre painter, in the same format as Thomas Knatchbull’s portrait (127 x 101.5 cm).15 The Knatchbulls placed a great premium on ancestor portraits and had been assembling them at Mersham Hatch since the early 16th century, some of them by high-calibre portraitists such John Michael Wright and Cornelius Johnson.16 Many of these portraits are of similar dimensions or have compositional elements in common, such as in an earlier, and somewhat smaller, portrait of a Bridget Astley (1570-1625) [11], where the sitter, like Thomas Knatchbull, rests her arm on a chair back.

The full-length, life-size image of Sir Norton is of a format that is not normally used for portraits of the Kent gentry and has no equivalent in terms of its scale in the Knatchbull portrait collection that had been brought together by the mid 17th century. It shows Van Hoogstraten responding to trends that had long been popular in English court portraiture. Knatchbull’s powerful and status-enhancing posture, with one hand propped on a walking stick and the other at his hip, arm akimbo, was used in respective portraits of Charles I by Daniel Mijtens I [12] and Anthony van Dyck [13].

11

circle of Robert Peake (I)

Portrait of Bridget Astley, Lady Knatchbull (1570-1625), c. 1590-1610

Sale London (Sothebey's) 2021-03-24, no. 108

12

and Hendrik van Steenwijck (II) Daniël Mijtens (I)

Portrait of Charles I Stuart (1600-1649), King of Great Britain, dated 1626 and 1627

Turin, Galleria Sabauda, inv./cat.nr. 395

13

Anthony van Dyck

'The King's Hunt', Portrait of King Charles I of England (1600-1649) with two squires and his horse, c.1636

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 1236

The two portraits were not apparently the only works by Samuel van Hoogstraten that the Knatchbulls owned. In September 1749 an inventory was taken of the contents of the family’s mansion at Mersham Hatch, upon the death of the fifth baronet, Sir Wyndham Knatchbull-Wyndham (1699-1749).17 The ‘Hall’ was mostly hung with family portraits, including Van Hoogstraten’s portraits of the Knatchbull brothers, which were placed on either side of John Michael Wright’s portrait of Mary Knatchbull (1610-1606), Abbess of Ghent, a kinswoman. Apart from portraits, the only other paintings in the room were the following:

A Large picture of Hugestrichen a

Painter and his wife -

One large prospective peice

It seems plausible that ‘Hugestichen’ is a mangled variation of ‘Hoogstraten’. However, more complicated is working out whether the ‘Large picture’ depicted ‘a Painter and his wife’ or whether two paintings were intended since the inventory frequently lists separate items in pairs on the same line. Similarly, is the ‘large prospective piece’, presumably an architectural painting, also by the Dutch painter? There is one little-known work by Van Hoogstraten, which has descended through generations of the Knatchbull family and is likely to have been one of the works listed in 1749 [14].18 It is inscribed with the artist’s initials and the date of 1665. This is a very unusual architectural fantasy in Van Hoogstraten’s output. We seem to be looking from some sort of watery grotto, through columns, to a villa and a garden with sculptures, and up towards ruined building on the hills beyond. One wonders if it was made on commission for Sir Norton, given his interest in the world of Antiquity and Italy. Or did he speculatively gift him the painting in anticipation of patronage, a strategy that he had recommended to young artists?19 Knatchbull had books on architecture and perspective in his library and, in 1626, he and two companions were given an official pass to travel for three years on the continent, with Italy most likely an essential component of their trip.20

14

Samuel van Hoogstraten

View of a garden terrace with statues, dated 1665

Private collection

Notes

1 Brusati 1995, p. 350, no. 19. Another portrait in Knebworth House (Brusati 1995, p. 350, no. 18) has been wrongly attributed to Van Hoogstraten. Roscam Abbing (Roscam Abbing 1993, p. 126, no. 27) even claimed that it was signed and dated 1663. The costume and its detailed treatment, as well as close parallels with the work of John Michael Wright (for example, his 1672 Portrait of Sir Edward Turner, London (Christie’s), 6 July 2007, no. 114), suggest a date in the early 1670s and an artist in the milieu of Wright.

2 Wright 2015, pp. 2-10.

3 Marshall 1999.

4 Foster 1891, p. 577.

5 Little is known of Thomas Godfrey’s later history. He had been bound over to keep the peace and in 1671 two kinsmen lost their sureties of £200 when he reoffended, having ‘assaulted and wounded a sad[d]ler in the town of Ashford’ (TNA, SP/290/fol. 233). He succeeded to the family estates at Lydd, Kent, on the death of his uncle, Sir Thomas Godfrey (1607-1684). An inventory was taken after his own death in August 1691, his possessions valued at over £454, but no paintings were listed (Kent History and Library Centre , Maidstone (KHLC), PRC/27/32/231).

6 On the close-knit relations between Kentish gentry families: Chalkin 1965, p. 191-217.

7 On the enlightened nature of portrait patronage in Kent: Tittler 2012, p. 156-162.

8 The sister of Norton and Thomas, Margaret Knatchbull (d.1618), had been the second wife of Nicholas Toke of Godington. Toke was the father-in-law of Thomas Godfrey.

9 Knatchbull-Hugessen 1960, p. 17-38; Henning 1983, vol. 2, p. 692; Keene 2004.

10 The first English addition was published posthumously: Knatchbull 1693.

11 De Beer 1955, p. 358.

12 London 1698. On the contents of the library: Pearson 2010.

13 Chalkin 1965, p. 210.

14 KHLC, U274/T48/20B.

15 Dorthea Honywood’s portrait, attributed to John Riley (1646-1691), was sold at Sotheby’s, London, on 7 June 2006, lot 223.

16 Long on loan at Maidstone County Hall, the Knatchbull portrait collection was largely disposed of at Sotheby’s, London, in 2006 and 2021. Sixty Knatchbull portraits are listed in Maidstone 1983, p. 1-9.

17 KHLC, U951/E14).

18 Brusati 1995, p. 366, no. 97, with wrong dimensions. The paper is first securely mentioned in the Knatchbull family papers in 1920 when a printed catalogue of the picture collection was made (KHLC, U951/Z54/3): ‘A Classical Landscape, with mansion and portico in foreground. By Samuel van Hoogstraten, 1665’.

19 Roscam Abbing 2013, p. 121-122.

20 The most relevant titles from his library are J.F. Niceron, La Perspective Curieuse (Paris 1638), S. Serlio, Tutte l’opere d’architettura et prospectiva (Venice 1600), and Vitriuvius, De Architectura (Strasbourg 1643). For the travel pass: Lyle 1934, p. 481.