1.4 Analysis of the Dataset

The dataset of 838 of Northern and Southern Netherlandish artist who travelled to Britain are analysed and compared here on three aspects.1 First, the distribution of the various disciplines of Netherlandish artists in Britain is examined. Then the departure dates to Britain are analysed and, finally, the stay dates of Netherlandish artists in Britain are provided.

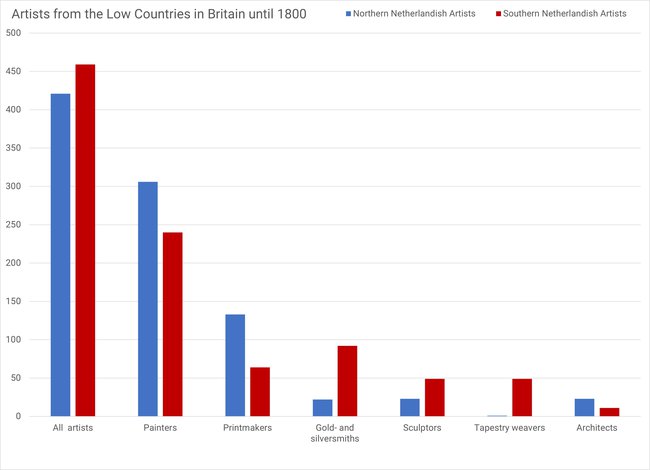

Added together, just slightly more artists from the Southern Netherlands travelled to Britain before 1800 (459) than from the Northern Netherlands (421) [16]. However, if we look at the disciplines of these artists, the Northern Netherlandish painters (306) were dominant over their Southern Netherlandish colleagues (240); the same goes for printmakers (133 versus 64) and architects (23 versus 11). Among goldsmiths and silversmiths, on the other hand, the Southern Netherlandish (92) prevailed over their Northern counterparts (22). There were also more Southern than Northern Netherlandish sculptors in Britain (49 against 23), while Netherlandish tapestry weavers (49) came almost exclusively from the Southern Netherlands. These differences are not surprising and correspond to the flourishing of disciplines in Northern and Southern Netherlands; however, the bar chart does give more insight into the proportions between them and our knowledge of them. As noted earlier, tapestry art and sculpture are so far underexplored areas of research. Further research is still needed for an overview of the demand for different art forms in Britain in different periods.2

It is known that Netherlandish artists were well represented among those working for the English court. Of 96 artists in the dataset, this is also documented, i.e. 11.5% of them were classified as 'court artists' in the database.3 Many others tried in vain to deliver to the court or found other patrons.As Sander Karst showed, it was not until the last quarter of the 17th century that Dutch painters in Britain worked more for the market, which had only then begun to develop.4

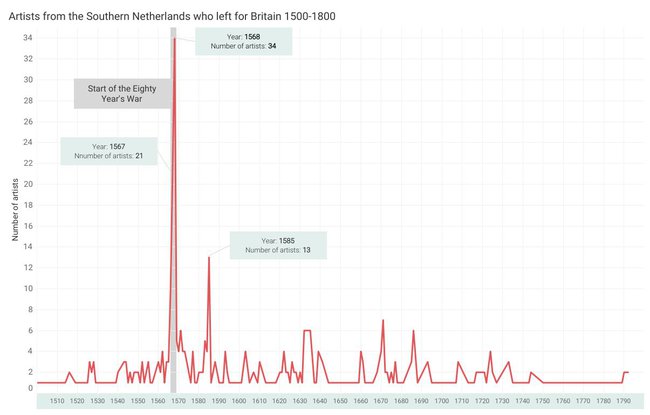

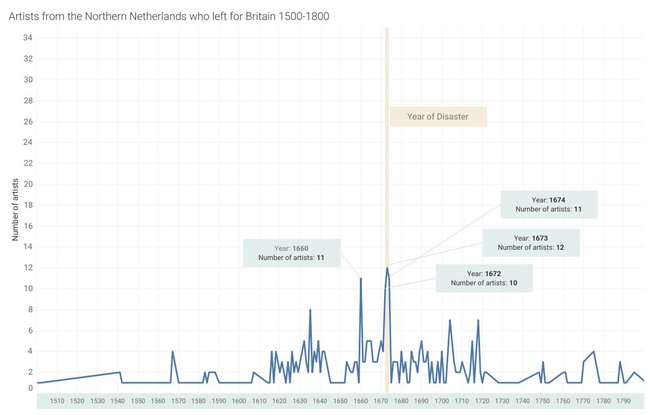

Statistics on the departure dates of artists from the Low Countries to Britain may give an indication of factors that prompted artists from the Low Countries to travel to Britain, again distinguishing between the Northern and Southern Netherlanders. For the visualisations of their departure dates, the first year of an artist's appearance in Britain was selected, if prior to that they had been either in the Northern or Southern Netherlands. Literally, therefore, these are not departure dates but arrival dates, which are here equated for convenience. For some artists, these dates may be impure because they may have travelled to Britain earlier, without being documented. According to the data in this dataset, only a few artists per year left for Britain in most years; here, a peak is referred to when more than ten artists are involved.

As expected, the departure dates of Southern Netherlandish artists to Britain differ greatly from those of the Northern Netherlands [17-18]. From the graph of the former, the huge peak of the year 1568 stands out; even in 1567, many Southern Netherlandish artists were already leaving for Britain. They had almost certainly fled from Ferdinand Alvarez de Toledo, duke of Alva (1507-1582), who, after the Iconoclasm (1566), was sent to the Netherlands by the Spanish king Philip II with an army to restore order. Alva arrived in Brussels on 22 August 1567, after which he immediately began the harsh persecution of Protestant heretics. Among those put to death is also an artist documented. By order of the duke, the house and possessions of the Mechelen painter Jan van den Eynde were seized by the authorities on 6 August 1568; he had by then been executed for sedition and heresy.5 Artists’ biographer Karel van Mander I (1545-1606) recounted that Willem Key (1515/6-1568), who was to portray Alva [19], died on the day the Counts Egmond and Hoorne were executed (5 June 1568), or possibly shortly before, because the painter had fallen ill after overhearing the duke say that they should die.6 The second, smaller peak in the graph in the year 1585 also points to a push factor, namely the occupation of large parts of Flanders by Alessandro Farnese in 1584 and subsequent Fall of Antwerp.

The departure dates of Northern Netherlandish artists to Britain also show two peaks, although these are modest compared to those of departing Southern Netherlanders. The first peak is that of 1660, the year Charles II (1630-1685) sailed from Scheveningen back to London to become king [20]. He had spent much of his exile on the continent in and around The Hague. In his wake, several Northern Netherlandish artists also crossed the North Sea. Yet the greatest peak among the Dutch is seen in the years 1672-1674, indicating the Disaster Year, as the beginning of the Dutch War (1672-1678) is called. The Dutch Republic was attacked by France, England and the dioceses of Münster and Cologne. From the east, enemy troops invaded the country in June 1672, but thanks to the efforts of Stadholder Willem III (1650-1702) from the end of 1673, the war was already no longer fought on the territory of the Dutch Republic. Many artists who decided to go abroad in these years chose Britain.7

That choice was encouraged by King Charles II's emphatic invitation to the inhabitants of the United Provinces to cross the North Sea with their families and possessions to settle in the British kingdom. Charles II's declaration dates from 12 June 1672, the day Louis XIV (1638-1715) invaded the Dutch Republic with his army, and was addressed to any Dutchman who wished to come to England, ‘either out of affection to His Majesty, or His Government, or because of the oppression they meet with at home from their Governors’, where Charles II also showed understanding for the Dutch who longed ‘to deliver themselves from the Calamity and Distress, into which the ill Councels of some prevailing persons in the Government of those Countreys have justly drawn them’.8 The invitation was distributed in the Dutch cities through pamphlets in English, Dutch and French. The king promised the Dutch migrants that their ships would be allowed through without difficulty, that they would be naturalised quickly and without cost, and that freedom of religion was guaranteed.

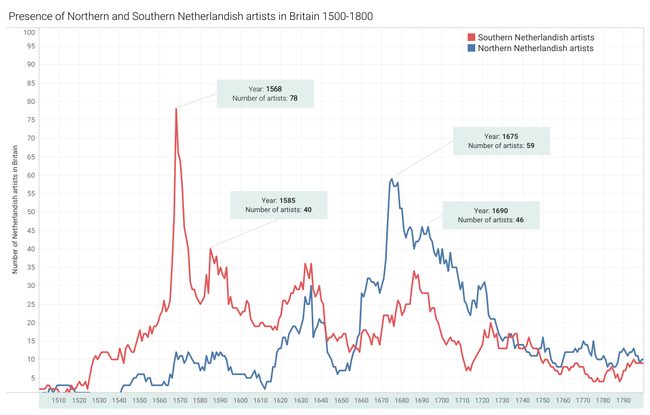

The visualisation of the presence of Northern and Southern Netherlandish artists in Britain [21] reveals more than the graphs of their departure dates. In terms of dominance, a clear dichotomy emerges. From the beginning of the 16th century until the year 1658, more Southern Netherlandish artists were active in Britain every year; from 1658 until the end of the 18th century, it was the other way around, with the exception of a few years in 1730s and 1740s.9

Apart from this change in dominance, some waves in the visualisation stand out. Apparently, the high number of Southern Netherlandish artists in London collapsed rapidly in 1568, only to rise again in 1585, which is related to the circumstances already discussed. Both waves took place during the reign of the Protestant Elizabeth I (1558-1603), during which foreigners in London were mostly able to work quietly and freely, except during periods of outbursts against them.10 From the coronation of King Charles I (1600-1649) in 1625 until the start of the English Civil War in 1642, a relatively large number of Northern and Southern Dutch artists were active in Britain; several of them were employed by the king, including Sir Anthony van Dyck, who died shortly before the outbreak of the civil war. That the year 1635 ranks relatively high in the visualisations is partly because the city of London did a very extensive census of foreigners in that year, documenting many of the artists present at the time.11 The number of Northern Netherlandish artists in Britain collapsed during the Commonwealth, in particular after the Navigation Act of 1651, which resulted in the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654) [22]. It is precisely after the death of the Puritan Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) and the Restoration that followed that the number of Northern Netherlandish artists in Britain suddenly rose sharply; this again did not apply so much to the Southern Netherlanders. The migration of Northern Netherlandish painters was probably stimulated in part by the collapse of the market for easel paintings after the peak of the 1650s, which left a surplus of active painters.12

The large influx of Northern Netherlandish artists who sought employment in the court circles of Charles II (1630-1685) in the early 1660s soon collapsed with the outbreak of plague in London, followed by the Great Fire of 1666. From the Year of Disaster, the number of Northern Netherlanders surged again: in the years 1675 and 1678 their numbers on British soil were highest. Although this then drops back somewhat, the number remains relatively high until a few years after the coronation of Queen Anne in 1702. The coronation of the Roman Catholic King James II (1633-1701) in 1685 caused a revival in the number of Southern Netherlandish artists in Britain. As Sander Karst has already noted, the arrival of Stadholder Willem III and his wife Mary Stuart II (1662-1694) as king and queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1689 onwards did not produce a significant influx of artists,13 but this probably caused the artists present to stay in Britain longer; we also see a slight increase in the chart in the year 1693. The last revival of activity both Northern and Southern Netherlandish artists in Britain coincides with the first decade of the reign the German-born George I (1660-1727), who was king of Britain and Ireland from 1714. So far, little research has been done on 18th-century artists from the Low Countries who were active in Britain.14

16

Bar chart of artists from the Low Countries in Britiain by discipline

Source: RKDartists, 7 March 2024

17

Artists from the Southern Netherlands who left for Britain 1500-1800

Source: RKDartists, 7 March 2024

18

Artists from the Northern Netherlands who left for Britain 1500-1800

Source: RKDartists, 7 March 2024

19

Willem Key

Portraity of Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, duke of Alva (1507-1582), 1568

Madrid (city, Spain), Fundación Casa de Alba, inv./cat.nr. P.2

20

Dancker Danckerts published by Dancker Danckerts

The departure of King Charles II with his fleet from Scheveningen to England, June 2, 1660, c. 1660

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-BI-6813

21

Presence of Northern and Southern Netherlandish artists in Britain

Source: RKDartists, 7 March 2024

20

Anonymous Northern Netherlands (hist. region) 1652

Cartoon of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) as the horrible tailman, 1652

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-79.497

Notes

1 For a comparison of mobility of Netherlandish artists to Britain compared to that in other countries, see Van Leeuwen (forthcoming).

2 My PhD will focus on clustering of discplines in certain periods (Van Leeuwen [forthcoming]).

3 The definition of the term and regulations for allocation of this fact in RKDartists needs further attention. The term 'court artist' is used for artists who were employed on a fixed salary and those who provided occasional work to the court; the latter may not have been applied consistently in the current data.

4 Karst 2021, p.

5 Neeffs 1876, vol. 1, p. 294-295.

6 On the attribution of the painting and the interpretation of Van Mander's text: Jonckheere 2011, p. 107-110, no. A42. Other versions of this portrait were painted or finished by his pupil Adriaen Thomasz. Key (c. 1545-c. 1589).

7 For effect of the Disaster Year on the mobility of Northern Netherlanders artists, see Van Leeuwen (forthcoming).

8 Karst 2013-2014, p. 27-28, citing the same declaration in the London Gazette of 10 June, see also https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/685/page/2 (consulted December 2020). Daalder 2016, p. 130 and fig. 82 (image of the title page of a Dutch-language copy of the pamphlet in the Royal Library, The Hague). See also Karst 2021, p. 170, 198-199.

9 See also Karst 2021, chapter 1, for a detailed description of the migration of Netherlandish artists to Britain and its backgrounds.

10 Scouloudi 1985, p. 41-42.

11 Scouloudi 1985, p. 96.Censuses of the 'Returns of Aliens' were conducted in the period from 1529 to 1639.

12 On the shrinking art market from 1660 onwards: Bakker 2011; Bok 1994, p. 121-127. According to Bakker, the change in interior taste was the main cause of the shrinking art market: preference shifted from easel paintings to decorative painting and gold or silver leather. The same was argued earlier in Horn 2000, vol. 1, p. 102-103. See also Rasterhoff 2017, p. 246-248. For a detailed description of the development, see Karst 2021, p. 42-45.

13 Karst 2021, p. 49.

14 For Netherlandish artists in Britain between 1780 and 1830, see the contribution of Quirine van der Meer Mohr in this publication.