9.4 John van Collema’s Legacy

Besides shaping the tastes of the English elite, John van Collema reaped rich financial rewards for his commercial success. Besides his Green Street premises, he acquired a second home in genteel Bayswater. It is tempting to speculate on how his homes were decorated, since wealthy merchants like Van Collema were consumers of the arts, as well as suppliers. Mireille Galinou suggested there may have been a ‘merchant aesthetic’, in the form of real-life touches mixed into the fanstasia of exotic goods that they imported.1 Van Collema was at his Bayswater home when he died at the age of eighty-four, on 10 September 1737. The London Evening Post noted that he was ‘carry’d from thence in a very pompous Manner’ to his burial at St Martin in the Fields (at the south end of St Martin’s Lane), leaving a ‘very considerable’ estate.2 His bequests totalled £7647, as well as £5000 of South Sea Stock and Annuities, and his household and trade goods.3 This was an extremely large fortune to have been amassed by a near-penniless immigrant orphan. He had also accumulated considerable social status through his wealth and connections, with two queens and a host of nobles among his customers, MPs and baronets in his extended family, and a duchess among his closest friends.

However, he did not forget his early struggles, nor the support he had received from the Breda orphanage. After the death of the Duchess of Chandos in 1751, a sealed envelope was discovered among her papers. It was addressed to ‘To the Gentlemen of the Vestry viz: Clerk, Elder and Deacon’ of the Dutch Church at Austin Friars, and marked ‘This must not be opened till after the death of the Lady Lidia Catherina Dutchess of Chandos’.4 Inside was another sealed envelope, and a letter of instruction, signed by Van Collema, beginning: 'It is my Request and Desire that you will be pleased to send this inclosed to the Gentlemen Rulers of the Citizens Children’s Hospital of Breda in Brabant and to observe their answer and order therein Vizt in the selling of the five thousand pounds South Sea Stock or Capital which is in the custody of you Gentlemen'. This codicil, dated 20 November 1736 (the same day that he made his will), left the £5000 of South Sea Stock, still intact (according to his strict instructions), to the orphanage where he and his brother had grown up. The administrators of the Dutch Church were to sell the stock, and remit the proceeds to Breda.

This final bequest was conditional upon certain terms, which he laid out in the aforementioned letter to the Regents of the orphanage.5 From the monies received, they were to immediately donate 5000 guilders to the Armkinderhuis [poor children’s home for non-citizens]. A further 5000 guilders, or the remaining capital, was to be laid up for benefit of the children of the Burgerkinderen-Weeshuis [orphanage for children of the citizens of Breda].6 On 13 October each year, every boy and girl was to receive a gift of half a rijksdaalder [rix-dollar], paid from the interest on the capital, and on their departure, every child would receive a gift of one hundred guilders. It was an act of kindness from a merchant who understood how a small amount of start-up capital could lead to a flourishing enterprise. The bequest was put into immediate effect, and to commemorate their benefactor, the Regents commissioned a large silver cup to be made in The Hague, engraved with Van Collema’s name, arms and cipher, and a special gathering to be held every 16 December, his baptism day.7 In the absence of a portrait (since Van Collema had never been painted), they commissioned a large carved wooden overmantel for the Regents’ room, in an exuberant rococo style, with Van Collema’s arms and a commemorative inscription [21]. Although the orphanage was rebuilt in 1889, the interior of the Regents’ room was preserved and reinstalled in the new building [22].8

John van Collema’s Anglo-Dutch biography and social and commercial networks underpinned his success as an India goods merchant, and mirrored the international nature of the goods he sold. As India goods travelled around Asia, on to the Dutch Republic, and were re-exported to England, it was Anglo-Dutch merchants who were able to exploit their connections to secure the best stock, and thus attract the wealthiest and most prominent customers [23]. In doing so, they not only facilitated the collecting and display of Asian imports, but helped to create and disseminate the fashion. Merchants were much more than passive suppliers of goods to customers. They shaped demand through the goods they offered, influenced the manner of display, and contributed to the development of a visual language through the goods they traded, showcased and sold. This case study of a single merchant-retailer, John van Collema, has demonstrated how elite collections of porcelain, lacquer and other Asian imports were built through frequent interactions between merchant and customer. It has also situated Van Collema within an extended network of Anglo-Dutch merchants, and shown the place of the individual within the teeming mass of global commerce. The VOC dominance of the East India trade in the 17th century, combined with the advent of an Anglo-Dutch monarchy in 1689, created the conditions under which Anglo-Dutch merchants could flourish [24]. The seeds of John van Collema’s ambition and entrepreneurship fell onto this fertile ground, and he was able not only to enrich himself personally, but to exert a considerable influence over the collecting and display of India goods in 17th and 18th century England.

21

Detail of overmantel with inscription, Regents’ Room, former Burgerweeshuis, Breda

Photo: Loek Tangel for the Rijksdienst.

22

Regency room with 18th-century gold-leather hanging, third quarter 18th century

Breda, Stichting De Zuidwester

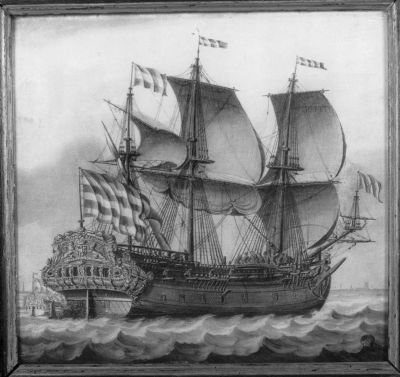

23

Cornelis Boumeester

De Oostindëvaarder 'Beyeren' van de VOC-kamer Delft, daarachter een spiegel met het wapen van Delft, c. 1700

Amsterdam, Het Scheepvaartmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A 3134

24

attributed to Hendrik Rietschoof

Dutch ships before the dock of the Dutch East India Company in Amsterdam

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Jurie Romke for tracking down Johan van Collema’s origins and legacy in Breda, and Stacey Sloboda for generously sharing her scholarship and helping me to navigate the complexities of the City of Westminster Archives.

Notes

1 Galinou 2004, p. xi.

2 London Evening Post 1536 (17-20 September 1737).

3 TNA PROB 11/685/124.

4 TNA PROB 11/788/335.

5 Amsterdam 1753, p. 58-62. Original correspondence relating to the bequest can be found in SB Notariële archieven Breda, Bron: akten, Deel: 0855, Periode: 1755, Breda, inventarisnummer 0855, 8 februari 1755, J.J. van de Laar, Allerhande acten (Minuten), 1755, aktenummer 17.

6 Van Collema’s mother was from Breda, which qualified him and his brother for admission to the latter. https://www.wiewaswie.nl/en/search/?q=Dirk%20van%20Hattem&advancedsearch=1 [accessed: 16 September 2022].

7 Amsterdam 1753, p. 60-61.

8 Kalf 1973, p. 172-173.