8.3 Copying the Cartouche and Atlantic Slavery

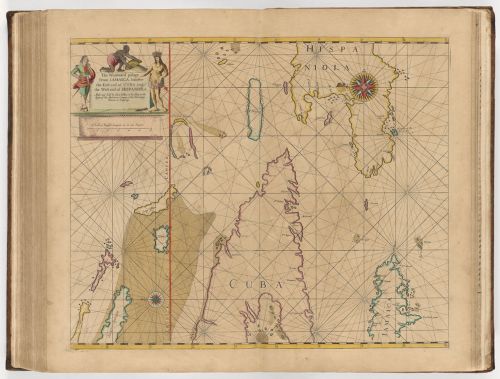

Among the decorative schemes John Seller lifted and recontextualised was Nicolaes Berchem’s cartouche, seen in Seller’s chart of Jamaica [12] in Atlas Maritimus (1675). The island of Jamaica, seen in the bottom left of the chart, was seized from the Spanish in 1655 as the consolation prize of Oliver Cromwell’s failed ‘Western Design’.1 The Dutch examples in Curacao and Brazil had shown that well-located territories in the Spanish Americas offered trade and plunder opportunities – a recognition evident in John Seller’s compositional choice, as Jamaica is seen near Cuba and Hispaniola. During the Interregnum, Charles made a conditional promise to return the island if Spain aided in the recovery of the throne. However, the Stuarts did not need Spanish assistance, and after the Restoration, Charles chose to exploit the commercial prospects of Jamaica [13], as the island was expected to yield high profits, both as a plantation, a slave-trading entrepôt and as a location for trade and plunder of Spanish colonies and fleets.2 Indeed, before the end of the 18th century, the Royal African Company enslaved and shipped more than 100,000 Africans to Jamaica, over a third of which were sold to Spanish colonies.3 The Spanish Americas offered the English lucrative opportunities, and although The Treaty of Madrid (1670) aimed to settle disputes in the West Indies, the Spanish remained an enemy.

The narrative of Spanish cruelty loomed large in the early English histories of Jamaica, especially in printed books and maps, as a justification for English territorial prerogatives and to mask the gross realities of Jamaica’s growing slave society. In John Seller’s chart, the figures representing the Americas and England - the man standing contrapposto with his hand on his hip - are positioned as equals. This composition conveys a cohabitation, and thus a relationship between Indigenous and English people in the West Indies, which was completely unfounded. In 1672, the cartographer Richard Blome (1635-1705) published the first English history of Jamaica, in which he described the Spanish destroying ‘all the Natives, or Indians, which according to calculation, did amount to about 60,000’.4 In 1707, Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) perpetuated an image of Spanish cruelty by claiming that he had ‘seen in the Woods [of Jamaica], many of their Bones in Caves, which some people thought were of such as had voluntarily inclos’d or immured themselves, in order to be starved to death, to avoid the Severities of their [Spanish] Masters’.5 Although the island was largely uninhabited, with only a few Spanish settlers and their enslaved Taíno (the Indigenous population) and African people, the English continued to enslave and indenture local and trafficked Amerindians.6 These people were forced to undertake a range of work in Jamaica, which probably included guiding early English surveyors around the island. Thus, Indigenous knowledge was used to further English cartography. The image of Spanish cruelty aimed to distract from English colonising activities, such as the enslavement and erasure of the Amerindian people.

12

John Seller published by John Seller

The Windward Passage from Jamaica, between the east end of Cuba, and the west end of Hispaniola, 1675

Cambridge (Massachusetts), Harvard Library

13

John Seller

Atlas maritimus, or A book of charts ; Describeing the sea coasts, capes, headlands, sands, shoals, rocks and dangers, the bayes, roads, harbors, rivers, and ports, in most of the knowne parts of the world …, Londen 1675, seq. 65

Harvard University, Harvard Map Collection

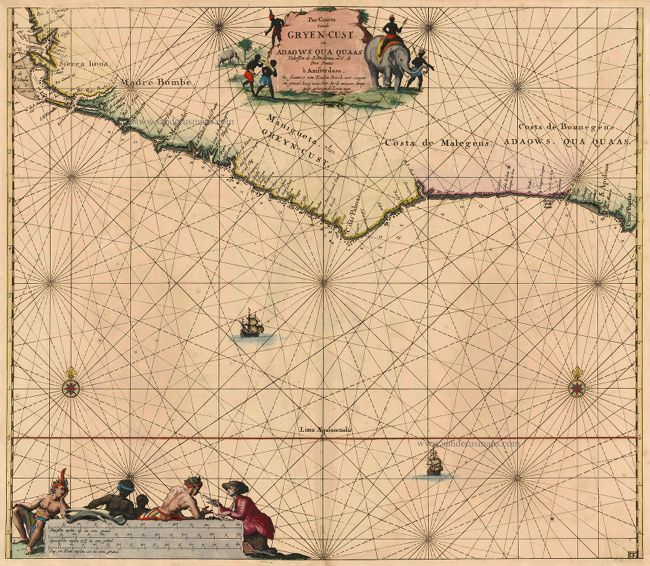

14

Johannes van Keulen (III)

Map of the Grain Coast - the western coast of the Gulf of Guinea, oriented to the North, published in 1683

Gent, Sanderus Antique maps & books

15

Johannes van Keulen (III)

Chart of the Gold Coast of Guinea, published in 1709

New Haven (Connecticut), Yale University

The figure kneeling on the inscription of the chart, rendered in black, represents an enslaved African person in Jamaica. By 1673, if not earlier, Jamaica was a slave society, with a population of 9,504 enslaved African people, with an additional estimated 1,000 residing in autonomous African enclaves in the hinterland, thus exceeding a white population of 7,768.7 These people had been exchanged and transported by the Royal African Company and independent merchants from Africa’s west coast to the Americas.8 The presence of figures depicting Africa in English maps and charts of colonial territories, such as the chart of Jamaica, signalled the trans-Atlantic slave trade. However, the text in Atlas Maritimus only mentions African merchants selling ‘their own people, whom they sell for Slaves, the Kings selling their Subjects, Parents their Children, and indeed all whom they can take or surprize, which are sent generally to the West-India Plantations’.9 The portrayal of European traders in Africa was another recurrent motif in cartouche designs, for example, Johannes van Keulen’s (1654-1715) charts of the Guinea coast show European merchants trading goods, such as a mirror, with mesmerised Africans [14-15] – a scene that conveys Dutch technological superiority. However, the role played by merchants in enslavement and Atlantic transportation remained absent from the visual language of cartography. John Seller’s cartography perpetuated an image of English virtuousness and enlightenment by shifting the onus of slavery away from English merchants. Moreover, by copying Dutch anti-Spanish propaganda, John Seller has placed even more distance between English colonial activities and the gross realities.

The contradiction between the visual and written languages of colonial spaces and the reality is a gap made even more stark by the contribution of Amerindian and African people in English cartography. In contrast to the subordinate position of the kneeling Black figure in John Seller’s cartouche, William Mayo’s (c. 1685-1744) map of Barbados, printed in 1722, is illustrated with figures of two Black men, likely enslaved, surveying the island using a waywiser, Jacob’s staff, and Gunter’s chain, assisting a white man, thought to be Mayo [16]. Mayo’s cartouche design points to the contribution of specialised knowledge from Indigenous and African people to the colonial project. But evidence like this is unusual, with most of the Amerindian and African figures in Anglo-Dutch cartography depicted as silent bystanders to European colonisation, with their contributions and resistance erased. However, the empty spaces in cartography, such as the mountainous interior of Jamaica in John Seller’s map [13], speak loudly of the continued resistance of autonomous enclaves that resided in these hinterlands, preventing English settlement and thus mapping. Anglo-Dutch cartographers shared a visual language that acquitted expansionism of cruelty by shifting the onus onto Spanish imperialism and remained silent on the contribution and resistance of Indigenous and African people in colonial spaces. As a result, cartographers promoted a palatable image of European colonialism and trade, which popularised colonial maps and charts to become objects worthy of collecting and display. This study has hopefully shown that colonial cartography, especially their cartouche designs, are worthy of critical and careful reading.

Detail of fig. 15

16

A new & exact map of the island of Barbados in America according to survey made in the years 1717 to 1721 by William Mayo

Engraving, hand-coloured, 470 x 560 mm

Royal Museum Greenwich, inv.no. G245:15/1A

Notes

1 Pestana 2017.

2 Swingen 2015.

3 Zahedieh 1986.

4 Blome 1672, p. 4.

5 Sloane 1707, p. 4.

6 The Jamaica Archives and Records Department, Spanish Town, probate inventories volumes 1-5 (vol. 4 is missing) contain numerous examples of ‘Indians’ owned by settlers as indentured or enslaved servants.

7 Sheridan 1973; Rugemer 2013; Zahedieh 1986. For the origins of the term 'slave society': Higman 2003.

8 Davies 1957.

9 Seller 1675, f. 6.