8.1 Dutch Artists and Cartographers Charting the World

This study will examine how 17th-century Anglo-Dutch encounters in cartography were shaped by European colonialism and the Atlantic slavery system, by focusing on the repeated use of a cartouche design by Dutch painter Nicolaes Berchem (1620-1683). In this period, European maps and globes played a significant role in promoting expansionism. These objects conveyed geographic knowledge and control of places and people which, even if unfounded, were powerful expressions of colonial ambition, and, through depictions of non-Europeans, reinforced racial hierarchies. The cartouche is the decorative scheme that often frames the map’s metadata – the title or patrons' names – and in John Brian Harley’s words, ‘serves to abstract and epitomize some of the meaning of the work as a whole’.1 The cartouches seen in colonial cartography, therefore, can be seen as representing the complex and asymmetrical power dynamics inherent to colonialism and slavery.

In the 17th-century Dutch Republic, cartography united excellence in science and art with the cartouche design meriting the hand of established artists. The Amsterdam-based Dutch cartographer Nicolaes Visscher II (1618-1679) began commissioning Nicolaes Berchem in the late 1650s, first to design the corners of his ‘Map of the World in Two Hemispheres’ (1658) with mythologised schemes of the four elements [1], and later for Visscher’s map of Asia.2 In 1657, Nicolaes Berchem produced two designs for Nicolaes Visscher’s map of America, Novissima et Accuratissima Totius Americae [2], of which the sketch for the bottom-left cartouche still exists [3]. The figures central to Nicolaes Berchem’s design include a man symbolising an Amerindian, wearing a feathered skirt and headdress, shielded from the sun with a parasol, and to his right, a kneeling man, possibly representing an African person, seen carrying a basket of gold grains to the foot of the scene. The inclusion of ethnographic images in maps of continents or of the world was typical of Dutch, and indeed, European cartography, popularised by Renaissance geographic allegories, such as Cesare Ripa’s (c.1555-1622) Iconologia, a handbook that included symbolic representations of America and Africa [4].3 However, the inclusion of subordinate depictions of African people, indentured or enslaved, departed from earlier ethnographic imagery and reflected 17th-century Anglo-Dutch interests in exploiting non-European natural resources and people.

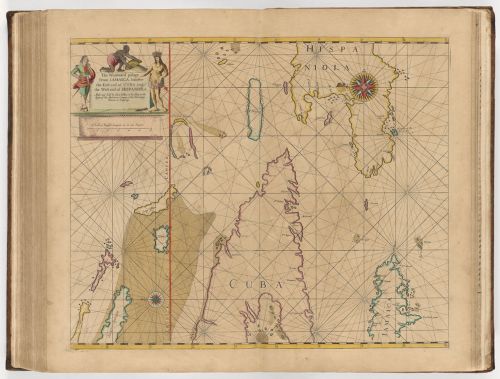

Benjamin Schmidt has written on the role played by cartouche designs in early modern European cartography, in shaping the ways that the non-European world was represented, seen, and imagined. In his study of the ‘exotic parasol’ motif, shown to be a frequent image in 17th- and 18th-century printed maps and books, Schmidt has discussed Nicolaes Berchem’s cartouche design, chiefly the parasol, as underscoring European colonial rule in the Americas.4 Nicolaes Visscher’s Totius Americae [2], and therefore Nicolaes Berchem’s design [3], were copied and printed by other engravers and cartographers for at least a century – by Dutch competitors Frederik de Wit (c.1629/30-1706) and Justus Danckert (1635-1701), and by the Scottish cartographer John Ogilby (1600-1676); it was even transferred to Africa’s gold coast by Hendrick Doncker (1625/26-1699) [5]. The design became a common motif for representing the ‘New World’. Indeed, Nicolaes Visscher’s cartography became so influential that his visual schemes were used for other cartographic objects, such as an English terrestrial globe [6], which includes the depiction of tribal conflict covering Brazil.5 However, scholars have not recognised the chopped and changed version by London-based cartographer and instrument maker John Seller (1632-1697) in his chart for ‘The Windward Passage from Jamaica’ (1672) [7], and, therefore, have also overlooked the related context of Atlantic slavery in Anglo-Dutch cartography. This study will focus on John Seller’s recontextualization of Nicolaes Berchem’s design in the face of Anglo-Dutch exchanges – defined by Caribbean competition and a shared cultural interest in propagating the image of Spanish cruelty.

1

Nicolaes Berchem

Jupiter and Juno (the element Air), before 1658

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 9824

2

studio of Nicolaes Visscher (II) published by Nicolaes Visscher (II)

Map of North America and South America, c. 1665

Whereabouts unknown

3

Nicolaes Berchem

Allegory of the Americas (verso), c. 1665

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 906441

4

‘Africa’, in: Iconologia di Cesare Ripa, Portland State University,

p. 67 pt

5

Hendrick Doncker (I)

Portolan chart of Guinea, c. 1670

New Haven (Connecticut), Yale University

6

Robert Morden, William Berry and Philip Lea

Terrestrial globe,

London 1690

H 540 mm, Ø 550 mm

Cambridge, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, no. 2691 (on loan from King’s College, University of Cambridge)

7

John Seller published by John Seller

The Windward Passage from Jamaica, between the east end of Cuba, and the west end of Hispaniola, 1675

Cambridge (Massachusetts), Harvard Library

Notes

1 Harley 1997, p. 161–220; Duzer 2023.

2 Bosters et al. 1989, p. 76-84.

3 Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia was first published in 1593, with a revised picture-rich edition in 1611. For the source of the image: https://exhibits.library.pdx.edu/items/show/248.

4 Schmidt 2011, p. 31–57.