7.2 Italianate Frames and the Emergence of Leatherwork and Kwab

Framed Italian paintings are documented as coming to the English court since the 1610s – and travel by courtiers and others to Italy would have familiarised them with contemporary and historic designs.1 For example, in 1621 Sir Balthazar Gerbier ‘arranged for two great frames to be made in Venice ‘after the Italian fashion’ for Titian’s great Ecce Homo and Tintoretto’s The Woman Taken in Adultery.2 Italian carved frames, part or wholy gilded, directly influenced sophisticated English patterns from at least the 1620s, for example the original frame on a portrait at Knole by Daniel Mijtens the elder (c. 1590-1648) of Lionel Cranfield, 1st Earl of Middlesex (1575-1645), signed and dated 1620 [3].3 The frame is of an Italian Renaissance cassetta type based on a classical architrave, originally with a brown painted background and oil gilded carved ornament, including Lionel Cranfield’s coat of arms in the bottom centre.4 The corners joints of its four oak members are mitred half laps, each secured with an original iron screw in the back edge. Dendrochronological analysis has been very rarely carried out on picture frames but was commissioned to confirm its date.5 This established the frame’s timber came from the eastern Baltic, dating to about 1620.6 The correspondence between the signed and dated painting, the dated timbers of the frame, and the sitter’s coat of arms comprise a unique survival from the reign of James I.

An Italian influence of centred foliate scrolls going out to the rope tied corners can be seen on the painting at Ham House of Queen Henrietta Maria (1609-69), inscribed ‘HR 1637’, painted after Sir Anthony van Dyck [4]. Examination of the original pine frame reveals its half-lapped constuction. The ornament of its four members is symetrical about their centres, with paired foliate s-scrolls and tripartite corners. The dates of manufacture for the pattern appears to be within the second half of the 1630s. Of the seven examples known, three contain paintings by or after Van Dyck but the earliest is on a portrait by Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen the elder (1593-1661).7 All of these examples have been overgilded but may originally have been blue and gold.

Examination of two full-length examples of the same pattern at Knole, both adjusted in size and over-gilded for their present paintings, has confirmed they were originally blue and gold. One of these, now on the portrait of Barbara Villiers, Countess of Cleveland, has remnants of its original blue background visible in areas where later gilding has flaked off [5-5a]. This demonstrates how the appreciation of Italianate part-gilded frames was eclipsed by that of all-over gilding once Leatherwork frames developed. Its pine front frame, joined with mason’s mitres, was nailed from the front onto its pine back frame that was joined with mortice and tenon.

3

Daniel Mijtens the elder

Lionel Cranfield, 1st Earl of Middlesex (1575-1645), signed and dated 1620

oil on canvas / painted and gilded oak frame

Knole, National Trust (painting 129887, frame 131340)

Image: Laurence Pordes, 2019

4

After Sir Anthony van Dyck

Queen Henrietta Maria (1609-1669)

oil on canvas / gilded pine frame, inscribed ‘HR 1637’

Ham House, National Trust (painting 1139955)

Image: National Trust

5

Peter Lely

Portrait of Barbara Villiers (1640–1709), Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland, c. 1662

Sevenoaks (England), Knole House, inv./cat.nr. NT 129855

5a

Detail of fig. 5, over-gilded pine frame, Knole, National Trust (painting 129855, frame 131422)

Image: Gerry Alabone, 2023

6

studio of Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of King Charles I (1600-1649), 1632-1639

Richmond (Greater London), Ham House

6a

Detail of fig. 6, frame in gilded oak

Image: Gerry Alabone, 2013

Simon has made the important observation of how the English Italianate scroll frame, of about 1637, original to Van Dyck’s portrait of Charles I Dressed in Black at Ham House, has the carved conceit of a rope running underneath the flat background and emerging across the centre of the corners and the top and bottom central masks ‘holding the leatherwork of the four sides together’ [6-6a], as can be seen at the top right and the top of the central mask.8 This conceit has also been applied, though less explicitly, on the original frame of about 1637 for Queen Henrietta Maria and the similar frame now on Barbara Villiers, where a rope emerges across the corners and runs under the central ridge of the scrolls around the frames.

An English Italianate scroll frame of about 1638 on another portrait of Henrietta Maria is likely to be original [7]. It has rope visible across its foliate corners, and the flat background rises into overlapping contorted scrolls, clearly in imitation of cut leather, combined with a foliate outer edge like the other frames described here.9 The central bud of each bottom corner of this frame has been lost. This frame and its pair have not been physically examined, but the good photographs online of their fronts and backs indicate they are unlikely to be replicas. The photographs indicate regilding, so it is unsure whether the frames were originally all-over gilded. The front-frame appears to be oak with horizontal butt joints, the back-frame is pine with pegged cross mortice and tenons and is nailed from the back onto the front frame. Stylistically and in terms of materials and construction both frames appear likely to be of the same 1637/8 date as their paintings. This rare pattern relates visually to the frames in figures 4 & 5 but additionally they have counterflowing scrolls and masks at the top and bottom centres – also ornaments derived directly from Italian frames.

These examples, and many other English Italianate frames of the period – though not yet ‘auricular’ – were already likely to have been considered by contemporaries as being carved at least partly in imitation of leather. This suggests that the concept of ‘Leatherwork’, in respect of 17th-century English frames, emerged possibly slightly before they incorporated distinctly ‘auricular’ characteristics. If this is so, then perhaps Leatherwork frames should be considered more distinctly from kwab, rather than them comprising two aspects of one common style, and both being appraised directly to the work of Netherlandish goldsmiths.

7

(After) Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641)

Queen Henrietta Maria (1609-1669) in a blue dress with a crown on a table beside her, about 1638

oil on canvas / gilded oak

sold from a family trust, Christie’s London auction, 17th December, 2020 (lot 139)

Image: Christie’s, 2020

8

Antonio Maria Viani

The Metamorphoses Gallery (ceiling detail), c.1595-1606

paint and gilding on plaster, Ducal Palace, Mantua

Image: Gerry Alabone, 2023

9

Antonio Maria Viani

The Metamorphoses Gallery (ceiling cartouche), c.1595-1606

paint and gilding on plaster, Ducal Palace, Mantua

Image: Gerry Alabone, 2023

It can be argued that Italian Mannerist grotesque designs, as well as kwab, influenced the development of English Leatherwork frames into auricular forms. International travel by designers, makers, and patrons throughout the 1620s and 1630s meant the latest continental ideas were also current in England. These influences included seeing Italian mannerist interiors and grotesques firsthand, such as the suite of four museum rooms in the Ducal Palace of the Gonzaga in Mantua known as The Metamorphoses Gallery from the Latin poet Ovid’s poem of the same name [8-9]. The Gallery’s mythological shape-shifting imagery was similar to the contemporary interest in exotic, rare and unusual examples of natural wonders such as fossils, minerals, and animals – a large collection of which it was decorated to display. 10 These intellectual interests and material forms were synonymous with the auricular.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) travelled and worked in Italy between 1600 and 1608, spending much of this time at the influential court of the Gonzaga. During his stay he would have witnessed the decoration of The Metamorphoses Gallery. The moulded plaster of its ceilings contains many cartouches with irregular inner and outer edges, scrolls, masks and the evocation of cut, twisting and overlapping skins – characteristics shared with later Leatherwork frames.

Rubens became a prolific ornamental designer as well as a painter; and he was greatly admired by Charles I who knighted by him during his stay in London between 1629 and 1630. Ruben’s oil sketch Horatius Cocles defending the Sablicium bridge', made in 1628, demonstrates the strong Italian design influence that continued in his work [10]. Anthony van Dyck, after working as one of Rubens’ principal assitants, also travelled to Italy, between 1621 and 1627, where he visited the main cities and Mantua. He moved to England in 1633, was also knighted by the king, and worked as court painter until his death in 1641, excepting a year spent in Antwerp over 1634/5. Therefore, he also had extensive firsthand knowledge of contemporary design from Italy and the Low Countries.

Italian frames continued to be imported into England, and the increasing influence of Italian and kwab designs and designers from the Netherlands, together created a confluence of design influences in London in the 1630s. Italian-derived English frame patterns became infused with kwab during the second half of the 1630s. Dutch glass painter Pieter Jansz. (c. 1602-1672) also made designs of auricular cartouches, including many for the important and prolific Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu I (1596-1673) whose published maps were exported widely. Jansz.’s drawing, Cartouche with a man with a pine trunk, made between 1630 and 1638 [11], shows how fictive frames in fashionable kwab designs of could be easily disseminated.

Another drawing by Jansz, Cartouche with two putti and a drapery, presently given a broad dating by the Rijksmuseum of between 1630 to 1672, has an oval cartouche with irregular inner and outer edges and screaming masks [12]. It has visual similarities to a celebrated early frame now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. This is the carved and gilded Leatherwork frame, by an unknown maker, is on Sir Anthony van Dyck’s last Self-portrait, of about 1640/1 [13-13a]. The frame has strong Italianate and kwab characteristics – motifs at its vertical and horizontal centres, irregular inner and outer edges, masks, scrolls, and the evocation of cut, twisting and overlapping skins.

This frame has been researched by Jacob Simon, who considers that Van Dyck possibly had a strong influence on frame designs in England.11 The frame is generally considered to have been made for the Self-portrait, however, it might be a few years earlier than the painting’s date of 1640/1, since it is a closely similar design to the frame in a representation of Van Dyck’s double portrait of himself with Endymion Porter in a Mortlake tapestry at Knole – and new examination of this tapestry’s border suggests it was not woven after about 1636.12 Such a date would make this one of, or the earliest known auricular Leatherwork frames and reinforces the importance of Van Dyck to frames in England.

10

Peter Paul Rubens and after Anthony van Dyck

Horatius Cocles defending the Sablicium bridge, about 1628

oil on panel

Liechtenstein princely collection (GE101)

Image: Liechtenstein princely collection

11

Pieter Jansz.

Cartouche with a man with a pine trunk, 1630-1638

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1898-A-3613

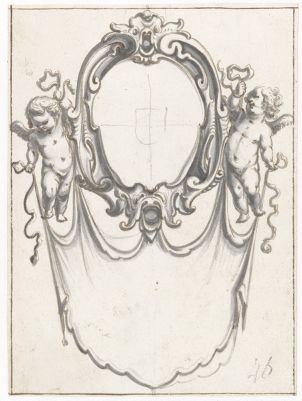

12

Pieter Jansz.

Cartouche with two putti and a drapery, 1630-1672

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1884-A-432

13

Anthony van Dyck

Self-portrait, 1640

Oil on canvas / gilded oak frame

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, no. NPG6987

Image: Alastair Johnson, 2009

13a

Back of fig. 13

Image: Alastair Johnson, 2009

14

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (I)

Portrait of Lady Coventry, 1630s

Oil on canvas / painted and gilded oak frame

Sheffield (South Yorkshire), Sheffield City Art Galleries, no. VIS.3718

Image: Gerry Alabone, 2022

15c

Detail of fig. 15b

Seven frames are now discussed [figs. 14-20] to demonstrate the swift incremental development of English Italianate frames to auricular. The first is a carved painted and gilded Sansovino frame original to Elizabeth, Lady Coventry by Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen I [14].13 It has an oak front-frame with horizontal mason’s mitres and a pine back frame nailed on from the front, with paired scrolls at the four centres, swags along the top, a volute at each end of the top and bottom member, the side members have round flower buds and the ends terminate with a plain base/capital.

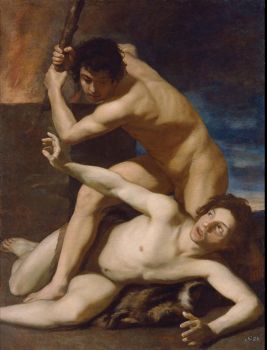

The painting of Cain and Abel by Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622), now in Vienna [15a], is represented within one of the views of The Brussels Picture Gallery of the Archduke Leopold Willhelm of Austria painted in 1651 by David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690) [15b]. The Cain and Abel is shown soon after its purchase from the dispersed Duke of Hamilton’s collection, in a carved painted and gilded Sansovino frame similar to fig. 14, with buds and seed pods, but brown and gilded, without swags along the top and with an angel mask at the centre [15c].

A pair of portraits by (circle of) Gilbert Jackson (active 1622-1640), auctioned from the collection at Faringdon House, in closely related frames, have not been physically examined but, from the good photographs online, they appear to be of about 1640, made with mason’s mitres and to have had their decorative surfaces stripped and refinished [16-17]. It is not possible to see whether they were originally painted and gilded, or over-all gilded.

The possibly original frame on the Portrait of a Young Lady dated 1643 is also in a carved Sansovino frame. It is similar to fig. 15 but narrower and with a mask at the top centre.The frame on a Portrait of a Young Gentleman, date unknown, has a slip-frame added between the painting and frame perhaps indicating reuse for this painting. The frame shows a close relationship with the Sansovino form of the last three examples, with paired scroll centres, scrolls at each corner, and masks at the top and bottom centres – however, the sillouette is more complex, the motifs look more supple, contorting away from the inner edge, and the seed pods are becoming claws. The Sansovino form had started to become auricular.

15a

Bartolomeo Manfredi

Cain and Abel, c. 1615

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv./cat.nr. 363

15b

David Teniers (II)

The Brussels Picture Gallery of the Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria (1614-1662), dated 1651

Petworth (England), Petworth House, inv./cat.nr. NT 486159

16

attributed to Gilbert Jackson

Portrait of a young lady, aged 15, dated 1643

oil on canvas / stripped and redecorated frame

Christie’s London auction, 29th January, 2019 (lot 128)

Image: Christie’s

17

attributed to Gilbert Jackson

Portrait of a young gentleman

oil on canvas / stripped and redecorated frame

Christie’s London auction, 29th January, 2019 (lot 128)

Image: Christie’s

Leatherwork’s shift towards the auricular is taken further on the frame now reused on The Battle of Liverno by Reinier Zeeman (c.1623/4-1664) [18]. This carved oak English Leatherwork frame, is likely to date from about 1640, and was extended slightly horizontally and cut-down vertically at its mason’s mitre corners for reuse on this painting, at the Rijksmuseum possibly during the 19th century.14 It was originally all-over gilded (now overgilded), which indicates that the frame in fig. 17 may also have once been all-over gilded. The paired ribbed scolls at the centres of its sides are very similar to those in fig. 17. Its forms appear yet more soft and fluid, seemingly puckering as the frame bends around the bottom corners, with forms very skillfully rendered in low relief, and with four areas of pierced ormament at each side. Interestingly, its top and bottom central masks extend over the painting, like the centres of the frame on The Perryer Family [figs. 26 & 27].

The much admired carved oak Leatherwork frame with its winged helmet, original to Venus with Mercury and Cupid ‘The School of Love’ painted about 1640 after Corregio (about 1489-1534) has been stripped, but several small areas of white ground layer from its original decorative surface survive in its interstices [19]. Stylistic comparison to other Leatherwork frames, such as fig. 18, suggests it would originally have been all-over gilded. It has many of the main characteristics of fig. 18, the top and bottom centre masks (a helmet/trophy cartouche at the top in this case, but not extending over the paitnting), paired ribbed scrolls at the centres of the sides, and the ornament seeming to crease as it folds around the bottom corners. However, it has no pierced carving. The oak front frame has horizontal mason’s mitres, and is nailed through the front onto its pine back frame joined by mortice and tenon. In relation to the other frames with it on the staircase at Ham House, Baarsen states: ‘Perhaps Christiaen van Vianen’s activities at court were not restricted to goldsmith’s work: he may have been commissioned to design works of art to be executed by others. Alternatively, his use of the auricular may have inspired artists working in different media’.15 However, the frames in Figs 14-19 show this frame’s design most likely evolved incrementally and quickly in England from an Italianate Sansovino pattern.

The portrait of Charles I by Van Dyck’s studio of the late 1630s at Kingston Lacey [20], exhibits some of the features of the last few frames, but while the side members retain perhaps a suggestion of concave centres they are no longer limited by symetry about them. These last seven examples [Figs 14-20] indicate the swift evolution of just one English Italianate frame pattern into the auricular – other types of English Italianate patterns made the same incremental development around the same time – together creating a new ornamental language for frames, directly related to, and yet quite distinct from, their predecessors.

18

Reinier Zeeman

The Battle of Liverno, 1653-1664

oil on canvas / gilded oak, Rijksmuseum, no. SK-A-294

Image: Gerry Alabone, 2014

19

After Corregio

Venus with Mercury and Cupid ‘The School of Love’, about 1640

oil on canvas / stripped oak

Ham House, National Trust (painting 1139671, frame 1140607)

Image: National Trust

20

After Sir Anthony van Dyck

Charles I (1600-1649), late 1630s

oil on canvas / gilded frame

Kingston Lacey, National Trust (painting 1257097)

Image: National Trust

Notes

1 Simon 2016.

2 Simon 1996, p. 52.

3 Also, the similar frame on (studio of) Daniel Mytens the elder, King James I (James VI of Scotland), about 1621, Sackville Collection (painting 129891, frame 131344). The Dutch painter Mytens moved to England in 1618 where his initial patron was the Earl of Arundel. In 1632 he was eclipsed by Anthony van Dyck as the leading painter for the English court.

4 Cassetta meaning ‘little box’. The coat of arms, which had been completely obscured by overgilding, was uncovered as part of a conservation treatment by Catherine Gray and the author in 2018.

5 Dendrochronology measures the tree-rings visible in end-grain and matches them to known data sets to provide dates and sources for the timber. As the frame was made to allow for disassembly, visible end-grain at the corner joints enabled analysis.

6 Tyers 2017.

7 Seven known examples of this pattern, based on the author’s images collection, are on: Cornelius Johnson, Nan Uvedal, Mrs Henslowe, 1635, Verney collection, Claydon House; Anthony van Dyck, Queen Henrietta Maria, about 1638 (?), Syon House, collection of the Duke of Northumberland; Peter Lely (?), Portrait of Charles I, with his second son, James, Duke of York, 1647 (?), A. K. Wheeler, Bonhams, lot 47, 1995, location unknown; and a frame auctioned at Bonhams, lot 97 (illustrated in catalogue), auction date and location unknown; Sir Anthony van Dyck, Lady Frances Cranfield, Lady Buckhurst, later Countess of Dorset, about 1637, Knole, National Trust (painting 129918, frame 131371); and Sir Peter Lely, Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland, about 1662, Knole, National Trust (painting 129855, frame 131422).

8 Simon 2013B, p.146-147.

9 One of two portraits in matching frames (lots 139 and 188), the other being (follower of) Sir Anthony van Dyck, King Charles I in armour, holding a baton, with the crown and a helmet beside him, about 1637.

10 The Gallery was designed by the painter and carver Antonio Maria Viani (1555/60-1629) who was the prefect of the Palace for Vincenzo I, of the House of Gonzaga, who started the decorative project in 1595, or maybe earlier, and continued until after 1606.

11 Macleod 2014, p. 26-27.

12 The Knole tapestry’s border contains ‘FC’ for Francis Crane (about 1579-1636), the first Director of the Mortlake Tapestry Works and, according to Wyld 2022 (appendix image no. 53, detail of a tapestry from Lyme), these letters were in use between about 1629-1636, when Crane died. The tapestry is in the collection of Lord Sackville. The original portrait by Van Dyck, Endymion Porter and Anthony van Dyck, about 1633-1635, oil on canvas, is now in the collection of the Prado (painting P001489).

13 The same type of frame also survives on its companion portrait Thomas Coventry, 1st Baron Coventry, signed and dated 1639, National Portrait Gallery (painting 4815). Both frames were overgilded when still at Rufford Abbey, and on Lady Coventry the black areas of the scheme have been repainted in a reversible medium by conservator Mike Howden, in about 2010, based on his visual examination of the earlier scheme.

14 Communication between the author and the former Senior Frames Conservator at the Rijksmuseum, Huub Baija, in 2020, agreed that the likely origin of the frame was England, based on its timber, design and decoration.

15 Baarsen 2018, 211.