5.1 The Van de Veldes as Court Artists at Greenwich

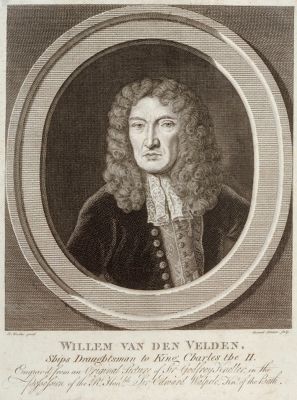

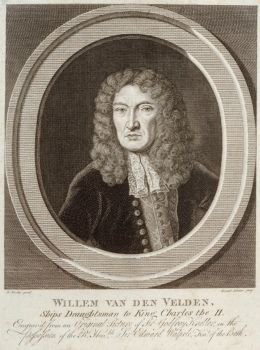

In March 1675, King Charles II’s Clerk of Works at the Queen’s House noted in his accounts the ‘makeing and hanging [of] III [three] paire of shutters of split deale for three windowes in a lower roome, at the Queen’s building next the Parke (where the Dutch Painters worke…)’.1 These Dutch painters were the marine artists Willem van de Velde the Elder (1610/11-1693) [1] and his son, Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633-1707) [2], who had arrived in England a couple of years earlier, in the winter of 1672-1673.

Dutch marine artists already enjoyed some reputation in Britain by this date, not least thanks to the remarkable series of Armada tapestries, designed by Hendrik Cornelisz. Vroom (1562/3-1640), which had hung in the House of Lords from 1651.2 After delivering the tapestries, which were woven in Brussels, Vroom travelled to England and met his client, Lord Howard of Effingham (1510-73), who had commanded the English fleet.3 Jan Porcellis (1584-1632) also spent some time in England, where he painted two panels for Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales (1594-1612), in 1612.4 A treatise on painting by Edward Norgate (1581-1650), a miniaturist and musician in the court of Charles I (1600-49) records an admiration in elite circles for both Vroom and Porcellis, ‘who very naturally describes the beauties and terrors of [the sea] in Calmes and tempests, soe lively express, as would make you at once in love with, and for-sweare the sea for ever.’5 Isaac Sailmaker (1633-1721) was another Dutch marine painter working in England prior to the Van de Veldes’ arrival — certainly by 1657, when George Vertue (1684-1756) records that he painted a commission from Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658).6 Nonetheless, the Van de Veldes invitation to the English court seems to have been without precedent, and speaks to a particular interest that the Stuarts had in Dutch art following their exile in the Dutch Republic.

The Van de Veldes – particularly Van de Velde the Elder – had achieved great renown across Europe before their journey to England. As well as powerful clients in the Dutch Republic, such as Admirals Cornelis Tromp (1629-1691) and Michiel de Ruyter (1607-1676), the Van de Veldes enjoyed the patronage of Cosimo III (1642-1723) and Leopoldo de’ Medici (1617-1675), and the Swedish Admiral Count Carl Gustaf Wrangel (1613-76).7 Before they migrated, the Van de Veldes had had a thriving family studio in Amsterdam. Van de Velde the Elder, was famed as a draughtsman and war journalist, who sometimes was employed to record the Dutch fleet’s activities at sea in situ - including several significant battles in the Anglo-Dutch wars – as sources for his famous pen paintings, while Van de Velde the Younger had trained with Simon de Vlieger (1600/1-1653) as an oil painter, producing canvas paintings in the family studio, sometimes in collaboration with his brother Adriaen van de Velde (1636-1672). These paintings sometimes took their father’s drawings as a source.8 The precise circumstances of their decision to leave Amsterdam for London during the Rampjaar are unknown, but the economic climate precipitated by that ‘disaster year’ necessarily impacted the market for art and prompted many artists to emigrate.9 In 1672, Charles II (1630-1685) issued an open invitation to Dutch citizens to relocate to England, promising religious freedoms, tax benefits and exemption from press (conscription), incentives communicated in a pamphlet printed in English, Dutch and French, which the Van de Veldes may have seen.10 As Remmelt Daalder has noted, it is also possible that the king or someone else at court issued them with a more personal invitation as the leading marine painters of their day.11

It is tempting to interpret the Van de Veldes’ move to England at the height of the Anglo-Dutch Wars as a coup for the British, within the naval rivalry that existed between the two nations at this date. Indeed, such a move from Amsterdam to London – ‘switching sides’ during the conflict – appears to the modern observer to be incredible. However, the notion of total war did not truly emerge until the Napoleonic period. Admiral Tromp was welcomed to the English court and made a baronet in 1675, and the Harwich packet continued to sail regularly during wartime, though the Dutch home port was moved from Helevoetslui to Den Briel.12 In the same vein, it is tempting to consider the Van de Veldes’ emigration to England a ‘prize’ for Charles II. Nonetheless, this interpretation probably constitutes an overstatement of Van de Velde the Elder’s position relative to the Dutch government, for whom he was only a participant in ad hoc missions to record specific battles. It also downplays the business imperative that is a hallmark of their entire careers, spanning both the Dutch and English periods. Indeed, the Van de Veldes had also been considering a move to Italy during the economic downturn in the Dutch Republic — an event that was not necessary, given the success that they found in England.13

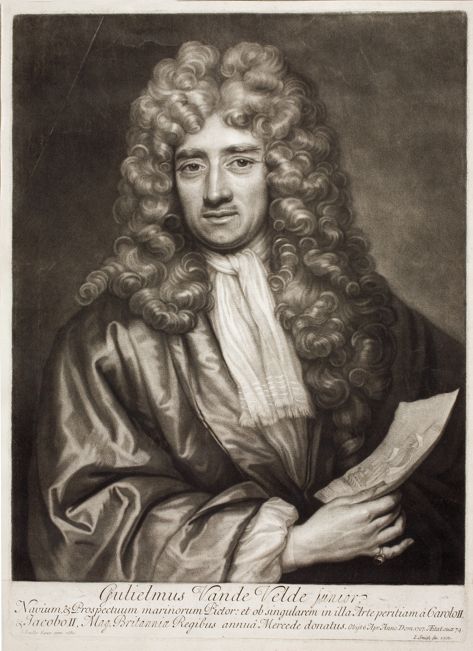

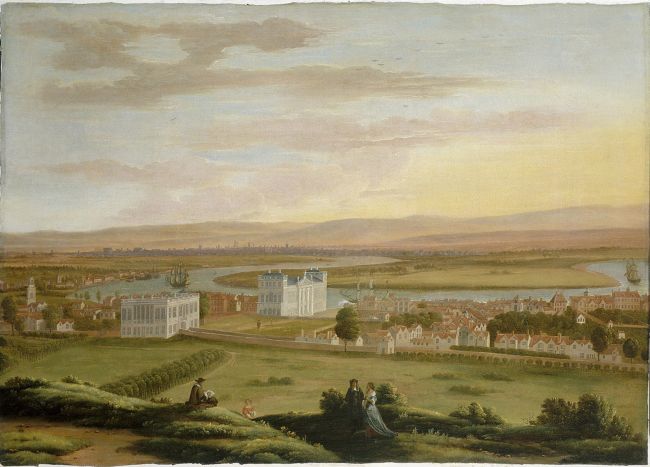

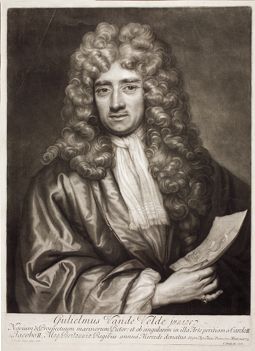

Whatever the precise motivation for their emigration, such was the kudos of having the Van de Veldes working for him in England, Charles II gave them a further inducement to stay, paying them a salary, via the Admiralty, of £100 each, and allocating them studio space in the building now known as the Queen’s House at Greenwich [3-4].14 In addition, Charles II’s brother, James, Duke of York (1633-1701), later King James II, awarded Van de Velde the Elder a further annual stipend of £50.15 The Van de Veldes’ combined annual royal salary in fact therefore totalled £250. As such, it appears to have outstripped that received by the Principal Painters to Charles II and Charles I, Peter Lely (1618-1680) and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), comparisons that speak volumes about the significance of marine painting as an expression of the Stuart kings’ self-image through British sea power.16 Certainly, the Van de Veldes were not the first Dutch marine painters to come to England, and nor were they the first to receive commissions from the English crown, but their arrival came at a time when imperial expansion and the control of maritime trade routes (as fought over in the Anglo-Dutch Wars) was high on the royal agenda. Indeed, the Van de Veldes had a certain advantage over other Netherlandish émigré artists in the hustle for royal favour, during this period when marine painting could be a tool as naval propaganda. The status maintained and developed by the artists in their new country is clear from the fact that they were both painted by society portraitist Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), another migrant artist from northern Europe. Though both portraits are now lost, they are recorded in prints [1-2] that – although in different media and produced decades apart – suggest that the original paintings may have been pendants.17

1

Gerard Sibelius after Gottfried Kneller

Portrait of Willem van de Velde the Elder (c. 1611-1693)

Greenwich, Royal Museums Greenwich, inv./cat.nr. PAD2659

2

John Smith after Gottfried Kneller

Portrait of Willem van de Velde II (1633-1707), dated 1707

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History

3

The Queen’s House, Greenwich, north elevation, facing into the former Greenwich Palace complex

4

Hendrick Danckerts

View of Greenwich and the Queen's House from the south-east, c. 1670

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. BHC1818

Unlike Van Dyck, Lely and Kneller, however, the Van de Veldes never received knighthoods for their service to the crown. Perhaps this was due to the fact that the volume of work actually commissioned by Charles II and James II was not ultimately as substantial as that produced by Van Dyck, Lely or Kneller, or perhaps it was related to their area of specialisation. André Félibien’s hierarchy of genres, published in 1667, does not mention marine painting explicitly, but he considered ‘the artist who imitates God by painting human figures … more outstanding by far than all the others’.18 Was marine painting, as attested by the fact that the Van de Veldes’ salaries were paid via the Admiralty, regarded more as a utilitarian genre, for documentary and illustrative purposes, more so than portraiture, for which Van Dyck, Lely and Kneller were primarily employed by the crown? This is borne out by the ‘old-fashioned’ style of a group of sea fights commissioned by James, when still Duke of York: as Daalder observes of these works, ‘compositional innovations that the son had introduced look as if they had been forgotten’.19 Even still, we might speculate as to whether, in other respects, royal patronage also afforded Van de Velde the Younger the freedom to aspire to transcend the hierarchy of genres, giving him the security to explore more ambitious compositions.20 His monumental painting A Royal Visit to the Fleet [5], almost certainly begun and at least largely painted in the Van de Veldes’ Queen’s House studio in the early 1670s, was probably the largest canvas he had attempted prior to then.21 Nevertheless, perhaps the fact that it never ultimately entered the Royal Collection is a significant litmus test for what Charles II and James II were looking for in a marine painting.

The Queen’s House was commissioned from Inigo Jones (1573-1652) in 1616 for Anne of Denmark (1574-1619) [6], queen consort to James I, and completed around 1635 for Henrietta Maria (1606-1669) [7], queen consort to Charles I. Although Charles II and James II in turn officially vested its use in their respective queens, Catharine of Braganza (1638-1705) and Mary of Modena (1658-1718), already by 1672 the Queen’s House was in effect no longer a royal residence but used instead for grace and favour purposes.22 During the Van de Veldes’ time in the Queen’s House, they shared the buildings with other important members of the court, such as the Huguenot John Chardin (1643-1713), then court jeweller to Charles II, and John Flamsteed (1646-1719), the first Astronomer Royal, who made observations from the Queen’s House while the Royal Observatory was being built. No other artists at the English court were allocated rooms in a royal building at this time, except for when they were decorating those spaces. It is unclear whether we should infer from this a privileged status amongst court artists, or whether this was simply a pragmatic solution. Without knowing the precise circumstances of the Van de Veldes’ migration to England, it is hard to establish whether their basing themselves in Greenwich was an independent decision they took themselves, or one dictated by the offer of the studio space in the Queen’s House.

Either way, Greenwich had various advantages to offer painters specialising in marines. As Karen Hearn has observed, court artists were generally exempt from the protectionist constraints imposed by guilds in the City of London, most notably the Painter-Stainer Company.23 Working in Greenwich, beyond the bounds of the City, the Van de Veldes would certainly have been free from these restrictions. Greenwich was also a sensible base for the Van de Veldes as marine painters because of its position on the ‘royal River’ Thames, between the royal dockyards of Deptford upstream and Woolwich downstream. They thus had ready access to the ships of the fleet, the core subject matter of the Van de Veldes’ work, or as Bainbrigg Buckeridge (1668-1733) put it, basing themselves in Greenwich enabled them ‘to be the more conversant in these things which were [their] continual Study.’24 It is significant in this context not only that their salaries were paid for by order of Admiralty, but that the Elder’s supplementary salary of £50 was awarded personally by James, Duke of York, who had been Lord High Admiral until 1673 and continued actively to assert his influence in maritime affairs subsequently.

5

Willem van de Velde (II) and studio

The royal visit to the fleet in the Thames estuary, 6 June 1672

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. 36-43

6

Simon de Passe published by John Sudbury and George Humble

Portrait of Anne of Denmark (1574-1619), queen of England, dated 1617

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. O.7.252

7

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Henrietta Maria de Bourbon (1609-1669), Queen of England, c. 1632

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden - Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv./cat.nr. 1034

The Queen’s House has had many functions since the Van de Veldes’ time there, as the residence of a prime minister’s wife, an orphanage and a school.25 Today, the building is once again a home for art contemporary to it, as the dedicated art gallery of the National Maritime Museum.26 The museum is thus the custodian of both the building in which the Van de Veldes had their English studio for almost 20 years, and also the world’s largest Van de Velde collection, which encompasses many oil and pen paintings, some 1,400 drawings and a tapestry. In 2023, to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the Van de Veldes’ migration to England, an exhibition showcased this remarkable collection in relation to the historic site of the Queen’s House.27 Central to this exhibition were two newly conserved masterpieces, each conceived in the Queen’s House. The first was the tapestry of the Battle of Solebay [8], the cartoons for which were laid out on the first floor of the building in the 1670s. The second was Van de Velde the Younger’s aforementioned Royal Visit to the Fleet [5], which was likely begun and at least largely painted in the Van de Veldes’ Queen’s House studio in the 1670s before its completion and sale some years later. Neither work had been on display for some decades, on account of their compromised condition. In addition to the physical exhibition, a digital resource showcased a project made possible thanks to a generous grant from the Getty Paper Project to digitise all 1,400 Van de Velde drawings in the collection.

The Van de Velde Studio – by which we mean both the physical ‘painting room’ the Van de Veldes occupied in the Queen’s House and the collaborative practice of the Van de Velde family and assistants – was at the heart of the exhibition. Though the Van de Velde collection at Greenwich is not indigenous to the Queen’s House in the sense of having stayed together with the site, many of these works would either have been created in the Queen’s House or at least ‘spent time’ in the house as studio assets. Similarly, although the collection was assembled in the 20th century primarily for its significance to maritime history, it also reveals the inner workings of a 17th-century artist’s studio, albeit a very specific one. To honour the collection’s significance – and specifically its significance within the history of the Queen’s House – the exhibition thus staged an evocation of the Van de Veldes’ studio in the very room where the Van de Veldes most likely worked, animating the space through a combination of original artworks, props and digital interventions [9].28 Despite a relatively short preparation period that began during the Covid-19 lockdowns, the planning process nonetheless produced various insights into the Van de Veldes’ studio practice in Greenwich, which arose through object-focused and site-led research, combined with the examination of archival records, contemporary sources and secondary literature. This contribution presents some of these observations on how the Van de Velde studio in the Queen’s House might have looked, and how it might have functioned practically.29

As Daalder has noted, the Van de Veldes’ migration to England prompted a new approach to working practices in the studio. In Amsterdam, the emphasis had been more on father and son’s complementary talents: the Elder in pen painting and the Younger in oils. In England, especially but not exclusively in the context of royal commissions, their working practice became more intertwined.30 Charles II’s instructions for their salaries makes this collaboration explicit:

‘Wee have thought fit to allow the salary of One Hundred Pounds per annum unto William Vandeveld the Elder for taking and making of Draughts of Sea Fights, and the like Salary of One Hundred pounds per annum unto William Vandeveld the Younger for putting the said Draughts into Colour.’31

8

tapestry workshop of Thomas Poyntz after design of Willem van de Velde (I)

The Burning of the Royal James at the Battle of Solebay, 28 May 1672, c. 1685-1690

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich)

9

Installation view of The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea, Van de Velde Studio, The Queen’s House

Their royal salaries were merely a retainer, which meant they were free to continue to cater to other clients when not occupied with royal commissions. The Elder did still make pen paintings following the move to England, but far fewer than previously, and it appears that he instead focused his efforts on drawings of ships and events for translation into paintings by his son (who in turn oversaw and delegated to assistants), and otherwise took on more of marketing and financial management role.32 It is conceivable that this shift was matched by a new approach to organising the studio space that differed from that in Amsterdam, but in the absence of further documentation, it is impossible to make such a comparison with any certainty. It is perhaps more constructive to reflect on the likelihood that the most relevant attribute of the Van de Veldes’ English studio - as with any artist adjusting to a new environment, both physical and commercial - was flexibility and adaptability. Where pertinent comparisons exist in aspects of the Van de Veldes’ studio set-up and practice either with other Dutch or English artists of the period, we have indicated them. However, the relative dearth of information regarding the latter, and specifically regarding court painters in England, means it is hard to assess how typical or atypical the Van de Velde studio at the Queen’s House was, how ‘Dutch’ or ‘English’ it was, or indeed how helpful such markers are at a time when so many Dutch artists were working in England and the English ‘art world’ was undergoing such a transformation as a result of their presence. We hope however that this contribution will prove a helpful point of reference in due course as further information about other artists’ studios in England comes to light.

Notes

1 Kew, WORK 5/25, f. 294 recto.

2 On the Armada tapestries: Rogers 1988.

3 Karel van Mander (1548-1606) describes Vroom’s visit in his Schilder-boeck: ‘At one time Vroom sailed from Zandvoort, went to the Admiral in England, and told him it was he who had drawn the pieces of the fleet, for which he was presented with one hundred guilders.’ Van Mander 1604, p. 288r.

4 Giltaij/Kelch 1996, p. 145.

5 Norgate 1919, p. 47.

6 Vertue makes unfavourable comparison between Sailmaker and the Van de Veldes, who he describes as ‘too mighty for him to cope with’. Vertue 1930-52, vol. 18 (1929-30), p. 71.

7 Daalder 2016, p. 85-127.

8 On their Amsterdam studio business: Daalder 2016, p. 65-83.

9 Karst 2021, p. 209.

10 Charles II’s declaration inviting Dutch citizens to resettle in England, 12 June 1672, printed by John Bill and Christopher Barker.

11 Daalder 2016, p. 130-31.

12 Daalder 2016, p. 132.

13 Agent Pieter Blaeu wrote to Leopoldo de’ Medici that Van de Velde had ‘resolved to go to England to see if he can succeed better there, with the intention of going thence to Italy if he cannot obtain any commissions.’ Letter from Pieter Blaeu to Leopoldo de’ Medici, 1 June 1674. Blaeu 1993, p. 279, no. 138.

14 Dated 12 January 1674, the order to pay the Van de Veldes each an annual salary of £100, to the Elder ‘for taking & making Draughts of Sea fights’ and to the Younger ‘for putting the [said] draughts of Sea fights into Colours’ was made by Charles II to his cousin, Prince Rupert, as Lord High Admiral. Kew, SP 29/359, f. 18 verso. It was endorsed in February that year. Kew, SO 7/40. It is worth noting that the award of an annual stipend did not always translate into its regular and timely payment, as was the case for many artists. In 1686 Van de Velde the Elder petitioned James II for the continuation of his stipend which had only been paid irregularly since 1674. Daalder 2016, p. 145, 217 and Robinson 1958-1974, vol. 1, p. 14, citing Kew T 1/2. According to Robinson, this was upheld and the stipend paid regularly until the end of James’ reign; in the winter of 1709-10 ‘Maudlin Vanderveld’ (presumably Magdalena Walravens, widow of Willem the Younger) was back paid the stipends for both her husband and father-in-law for the quarter ending June 1683. Robinson 1958-1974, vol. 1, p. 14. The Van de Veldes did not live in the Queen’s House but rather in the nearby East Lane, the location of present-day Eastney street, a few steps south east of the Queen’s House, outside the bounds of the palace complex. Greenwich 1982, p. 17.

15 In a letter from to Leopoldo de’ Medici date 20 July 1674, Pieter Blaeu writes: ‘the King of England had had the goodness to grant [Van de Velde the Elder] a salary of 100 pounds sterling a year … and that the Duke of York had also promised to pay him 50 pounds sterling a year, and all that quite apart from the remuneration that he would receive for each painting.’ Cited in Daalder 2016, p. 143.

16 Both Lely and Van Dyck received an annual stipend of £200 each. Daalder 2016, p. 145.

17 John Smith’s mezzotint after Kneller’s portrait of the Younger measures 351 mm x 256 mm, while Gerard Sibelius’s engraving after Kneller’s portrait of the Elder measures 240 mm x 180 mm.

18 André Félibien, Preface to Conférence de l’Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (1669), quoted in Edwards 1999, p. 35.

19 Daalder 2016, p. 149.

20 We are grateful to Christine Riding for this idea.

21 Daalder 2016, p. 156. The circumstances of A Royal Visit to the Fleet’s commission and eventual sale are not certain. It has traditionally been presumed to be a royal commission, which is what is suggested by George Vertue in his early 18th-century notebooks (Vertue 1929-1930, p. 70-71). It is also however possible that it was begun speculatively with a royal purchaser in mind. The painting was first signed and dated by the Younger in 1674, and received further additions some years later, at which point the artist adapted the painting’s date from 1674 to 1684 or possibly 1694. The painting was then sold privately and did not enter the royal collection.

22 On the history of the Queen’s House during the Van de Veldes’ tenure: Bold 2000, p. 80-82.

23 Hearn 2009, p. 39. On artists in London: Edmond 1978-1980, Foister 1993 and Kirby 1999, p. 8-10.

24 Buckeridge 1706, p. 473.

25 Van der Merwe 2017, p. 88-109

26 The National Maritime Museum is also known as Royal Museums Greenwich, which acts as custodian for the National Maritime Museum, Queen’s House, Cutty Sark and Royal Observatory.

27 The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea took place at the Queen’s House, 2 March 2023 – 14 January 2024.

28 The reconstruction of the Van de Velde studio was made possible with thanks to the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, the Tavolozza Foundation, the Paul Mellon Centre and a Paper Project grant from the Getty Foundation, among other generous supporters.

29 This research and the 2023 Queen’s House exhibition is indebted to Remmelt Daalder, both for his superb monograph (Daalder 2016) and for the generosity with which he has shared his expertise on all things Van de Velde with us. Like any scholar of the Van de Veldes, we have drawn widely on the seminal work of Michael Robinson in his various catalogues (including Robinson 1958-1974 and Robinson 1990), and on the invaluable catalogue of the 1982 Van de Velde exhibition (Percival-Prescott/Cordingly 1982), organised by Westby Percival-Prescott and David Cordingly. As reflected in the references below, Katja Kleinert’s research on 17th-century Dutch painters’ studios was instrumental in our ‘staging’ of the Van de Velde studio within the exhibition, and we are similarly most grateful to Leonore van Sloten at the Rembrandthuis for her guidance. We also owe special thanks to Pieter van der Merwe, for sharing his unparalleled knowledge of the history of Greenwich. The exhibition was further indebted to technical and conservation-based research projects into the Van de Velde drawings and paintings at Greenwich conducted by Clara de la Peña McTigue, Emmanuelle Largeteau, and Kendall Francis. The major monographic exhibition mounted by the Scheepvaartmuseum, Amsterdam, in 2021 was an important point of reference.

30 Daalder 2016, p. 148. Daalder cites the example of the series of sea fights now in the Royal Collection which exhibit the hallmarks of designs by the Elder, rendered in colour by the Younger. Similarly, we might imagine that the Elder designed the cartoons for the Solebay tapestry series with the Younger applying the colour.

31 Order from Charles II to the Board of Admiralty, on 12 January 1673 OS (22 January 1674 NS).

32 Daalder 2016, p. 162.