4.4 Patrons of Perspective Paintings

Van Hoogstraten’s principal patron when he arrived in London was Thomas Povey (1613/14-c. 1705).1 In terms of finding a powerful advocate who would promote his career, he could not have chosen better. Povey held a range of political and court appointments and was an acknowledged expert on colonial affairs.2 However, despite his wealth and influence, he had a reputation for poor accountancy skills and inefficiency, which saw him lose two lucrative posts in the 1660s as treasurer to the Duke of York and to the Tangier Committee.3 The latter role he resigned in favour of the diarist Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), who admired Povey’s good taste and used his contacts with painters to acquire pictures but was scathing about his overblown personality and business acumen.4 Povey was one of the original members of the Royal Society in 1663 and demonstrated a particular interest in technical art history, presenting a paper on tempera painting, taking members to visit artists such as Robert Streater (1621-1679) in their workshops, and encouraging the Society to produce a book-length publication on the history of various painting media.5 As well as being a noted collector, he also seems to have had knowledge of architecture, and had a role in overseeing the reconstruction of Euston Hall, Suffolk, the residence of Henry Bennett (1618-1685), the 1st Earl of Arlington.6 With some others he attempted in 1667 to revive the fortunes of the Mortlake tapestry manufactory. Povey’s house in the north-west corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where he lived between 1659 and 1679, was widely celebrated and is repeatedly mentioned by Pepys in his diary for some of its unusual features.

We know that Van Hoogstraten painted two perspectives for Povey [18-19]. Although there is no direct documentation for these commissions, both paintings are firmly listed in the early 18th century, among the possessions of Povey’s nephew, William Blathwayt (1649-1717), at his new home, Dryham Park in Gloucestershire. Pepys was fascinated by perspective paintings that he saw in Povey’s London house, although he never mentions Van Hoogstraten’s name. His response to the View Down a Corridor has been thoroughly rehearsed in the literature: in January 1663, shortly after the painting was completed, Povey opened his closet door for his guest, to reveal the illusionistic painting within, and Pepys needed to persuade himself that ‘there was [was] nothing but a plain picture hung upon the wall’.7

But what has escaped notice is that Pepys mentions a ‘new perspective’ in Povey’s closet in July 1664. Some months later, he writes about ‘pictures [plural] of perspective’ in the same location, describing them as ‘strange things, to think how they delude one’s eyes, that methinks it would make a man doubtful of swearing that he ever saw anything’.8 There are good reasons for believing that the View of a Courtyard is this new painting. It is indistinctly dated 1664 and is approximately the same height and twice the width of the View Down a Corridor. Both paintings have the same plunging perspective and the horizon line in each case is about halfway up the picture.

While substantial in proportions, these paintings by Van Hoogstraten would have functioned well within the narrow confines of a closet if hung from ceiling to floor, or perhaps elevated on a step, creating a sense of coextensive space and making the room less claustrophobic. The two paintings do not represent a continuous scene, with one taking us into a succession of rooms on a domestic scale and the other leading into a courtyard with a more palatial building and an imposing Ionic colonnade. Nonetheless, there are elements in common like the dog (one active, one dormant), the shy, peering cat, Ionic capitals and columns, and classical busts. Both paintings seem to have been designed to reward viewing from a distance, as well as at close quarters. We can imagine the View Down a Corridor being placed on the wall opposite to the entrance door, and the visitor initially apprehending it from a slight distance, where the illusion is at its most convincing.9 And then when he or she gets closer, and looks up, they experience the tilted-up bird cage as a fully three-dimensional object suspended in space. It is also at that moment that the conceit collapses and we realise that it is nothing but a ‘plain picture’ on a wall. The second work, hanging on an adjoining wall, would have operated in the same way. Here, when we reach the painting, we have the disconcerting sensation of looking down at the dramatically foreshortened steps closest to us that seem suddenly to fall away to the lowest level of the courtyard. On one step a playing card has been enigmatically left for the viewer to find – just like the discarded letter on the staircase or the card under a table in the other painting.

The word ‘closet’ designated a small room in the seventeenth century, which could have various functions dependent on the owner’s interests and its location within the house.10 Closets attached to bedrooms were generally private spaces intended for quiet introspection, prayer and study. Other closets were probably larger in scale and functioned as repositories for books, scientific instruments and precious objects, and as places of social interaction. To be invited into a closet was a sign of affection and a privilege. The most important source for the early modern closet is unquestionably Pepys’ diary.11 Pepys had several closets in his homes at various times and expended a great deal of effort in furnishing and organizing their contents, and in showing off them off to friends and guests. He also recorded his impressions of the closets he visited in other houses and palaces. There was always something worth seeing in these private spaces that would engender awe and conversation; in Pepys’ case, apart from books and pictures, he also quite revoltingly displayed (in a special case) a stone recently removed from his bladder by a surgeon.

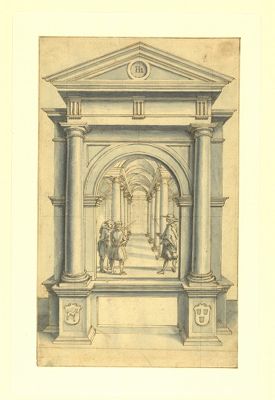

It is worth speculating if other perspective paintings by Van Hoogstraten are best understood in terms of the contemporary notions around the closet and the desire to display works there that created a sense of wonder and provoked debate. Many of the figures in these works are shown reading; books and their contemplation was particularly associated with closets. The frontispieces of books from this period were also often architectural in format [20] and involved similar framing devices as to those used by the artist.

18

Samuel van Hoogstraten

View of a courtyard with a man reading, dated 1664 (?)

Dyrham, Dyrham Park, inv./cat.nr. NT 453771

19

Samuel van Hoogstraten

View in a corridor of a private house, dated 1662

Dyrham, Dyrham Park, inv./cat.nr. NT 453733

20

Hendrik Hondius (I)

Design for a frontispiece, shortly before 1622

Mettingen, Draiflessen Collection, inv./cat.nr. 33

21

Samuel van Hoogstraten

View of a courtyard with a man reading, between 1662-1667

Private collection

22

Samuel van Hoogstraten

A boy catching a bird in the colonnade of an imaginary palace, 1662-1667

Private collection

Unfortunately, we know very little about the original patrons of the artist’s other perspective paintings. Christopher Brown suggested that there had been a ‘major decorative scheme by Samuel van Hoogstraten’ at Burley-on-the-Hill and associated these paintings with Daniel Finch (1647-1730), 2nd Earl of Nottingham, who had built this house in Rutland in the 1690s.12 However, there is no evidence that there was ever a suite of works by the artist in this country house and, moreover, Finch had not yet reached the age of majority, spending the years 1665 to 1668 on a Grand Tour of Europe. However, one painting by the Dordrecht artist can be traced to Burley-on-the-Hill [21]. An inventory of 1772 lists ‘A Picture over the Chimney of a Man reading & a dog by him in an open building, the perspective good’, which was hanging in the ‘Salon Below’.13 The most likely patron for this architectural painting was Heneage Finch (1620-1682) [23], 1st Earl of Nottingham (from 1681), and father of Daniel.14 During Van Hoogstraten’s stay in London, he was a baronet, a MP and Solicitor General before becoming Lord Chancellor in 1675. His original family seat was in Eastwell, Kent, and he belonged to the same gentry milieu as the neighbouring Godfreys and the Knatchbulls. A Young Man Reading in a Courtyard has always been regarded in the literature on Samuel van Hoogstraten as a pendant of a closely related work [22].15 This misunderstanding seems to extend from their identical dimensions and the fact that they currently belong to the same private collection. Both paintings found their way separately into this collection and, in fact, the view in each is framed by stone arches of a different form and decoration.16

Evidence for other early owners of Van Hoogstraten’s perspective scenes is scant. One possible client was the Swedish resident in London, Sir Johan Barckmann (Baron Leijonbergh) (1625-1691), who was a member of the Royal Society from 1667. Pepys tells us that he met Povey in November 1668 at the home of Barckmann in Convent Garden and that they dined together. After dinner, the diarist saw a ‘piece of perspective’ in his host’s ‘upper room’ but proclaimed it ‘much inferior to Mr. Povey’s’.17 The fact that Pepys likened Barckman’s painting to one of Povey’s might suggest that they were by the same artist, but we can only speculate. What is certain, though, is that Van Hoogstraten remained in contact with his English clients and may have continued to supply them with works. On 18 August 1671, Povey wrote to William Blathwayt, who was at that time a clerk in the English embassy at The Hague, asking him to provide directions to Sir John Williams (1642-1680), who was spending several weeks in the Low Countries.18 Among the places that Blathwayt thought his ‘verie good friend and neighbour’ should visit was ‘Hoogstratens house, my Perspective Painter’, as well as a glass manufactory in The Hague and the automata at the Amsterdam doolhoven. His uncle added that Williams ‘hath travailed and oft gets Curiosities, and Hee hath a Purse capable of Serving his Inclinations’.

23

Peter Lely

Portrait of Heneage Finch (1621–1682), 1st Earl of Nottingham, Lord Chancellor of England, 1666

Kenwood House, English Heritage, inv./cat.nr. 88282731

Portraits with real or imaginary architecture had been popular in court and royal circles in the early Stuart period, and in one painting showing a couple in Westminster Abbey [24], Van Hoogstraten alludes to this pictorial type.19 The well-dressed man and woman stand in the south transept of the church, the coronation and burial place of kings and queens since the 11th century. They are surrounded by references to almsgiving. In the central doorway of the north transept, a kneeling beggar accosts a visitor to the church. With a rapidly expanding population, Westminster parishes like St. Margaret’s, which surrounded the Abbey, had to contend with growing numbers of paupers or parishioners in desperate straits, despite the presence in this area of Whitehall Palace, Parliament and the houses of aristocrats and gentry.20 Directly above the man’s head is a plaque which reads ‘Blessed is he that Considereth the Poor’, taken from Psalm 41. The plaque, as well as the shrine to the Virgin Mary, the altarpiece in a side chapel and the niched sculptures of saints under the rose window, did not exist in Westminster Abbey at this time.21

It may be too far-fetched to speak of a portrait here, but the couple in Van Hoogstraten's painting seems to be referring to Heneage Finch and his wife, Elizabeth Harvey (1627-1676), niece of the famous physician William Harvey (1578-1657). As has been indicated, Finch is likely the original owner of A Man Reading in a Courtyard. Although Van Hoogstraten represented the couple as fair-haired, there is a physiognomic resemble between the individuals in Van Hoogstraten’s painting and known portraits of Finch [23] and his wife.22 Finch had a reputation as a charitable individual. In August 1665, he made a personal donation of £40 towards indigent plague victims in the parish of St. Margaret’s, one of the largest recorded.23 In Ravenstone, Buckingshire, where Finch had a country house, he endowed the vicarage, provided funds towards the maintenance of the local church, and established an almshouse for twelve elderly impoverished individuals, divided equally between male and female members of the Church of England.24 An inscription on his tomb in the local church praised him as a man of ‘most exemplary piety, large and diffusive charity, not unequal to any that gone before him, and an eminent example to posterity’.

Van Hoogstraten’s church interior, which dates to around 1665, may have been painted to commemorate Finch’s act of generosity to the sufferers of the plague in the vicinity of Westminster Abbey. Alternatively, it may have been intended as a more general plea for voluntary charitable donations — hence the more general representation of the couple. In the Middle Ages the Benedictine monks of the Abbey were known for the scale of their almsgiving and considerable sums were dispensed in institutional forms of charity and in doles directly given to the needy.25 With the dissolution of monasteries, a new welfare system came into play, administered by the parishes, and financed through a tax on property, known as the poor rate. However, these compulsory taxes were slow to reach the level of pre-Reformation charitable spending by the monasteries. Some members of the elite managed to evade paying the poor rate, while others who did were less inclined to give money at various collections for the poor or to make charitable bequests in their wills.26 In Van Hoogstraten’s painting we see evidence of the more structured and discriminate way of almsgiving, which was now under lay control. A woman holding a baby, seated on a step in the middle distance, is deep in conversation with a black-clad man. He has a folio volume under his arm and may be a churchwarden, who is hearing the woman’s petition for charitable relief. In this period, churchwardens could either refer deserving cases to parish overseers for investigation when pensions were involved, or they could dispense funds from their own resources.27 By including references in the background to the real of imagined Catholic past of Westminster Abbey, Van Hoogstraten (or Finch) may be suggesting that the tradition of almsgiving had continued unabated under the new Anglican administrators of the church.28 The part of the Abbey where the couple is standing, close to the tomb of Chaucer, may have been particularly associated with charity. From 1586, an annual dole to the poor was distributed here according to a will made by the gardener John Varnam (1540-1586).29

24

attributed to Samuel van Hoogstraten

View in the north transept of Westminster Abbey in London, c. 1663-1664

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum, inv./cat.nr. DM/984/588

24a

Detail of fig. 24

Notes

1 I am preparing an extensive article on Povey entitled ‘In and Out of the Closet: Samuel van Hoogstraten’s architectural paintings for Thomas Povey’.

2 Murison 2004.

3 Callow 2000, p. 118-123.

4 Pepys shamefully reneged on his agreement to compensate Povey for passing the lucrative position to him: Tomalin 2002, p.144-147.

5 Birch 1756-1757, vol. 2, p. 84, 107, 111, 227-231, and 235; Hunter 2013, p. 98-100.

6 Oswald 1957, p. 102-103.

7 Latham/Matthews 1971-1983, vol. 4, p. 26.

8 Latham/Matthews 1971-1983, vol. 5, p. 212 and 277.

9 At Dryham Park, the painting has always been effectively displayed at the end of a sequence of rooms.

10 Stewart 1995; Bobker 2020, p. 1-44.

11 Loveman 2015, p. 252-263.

12 Brown 1993, p. 27.

13 The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (ROLLR), DG7/Inv. 4.

14 Yale 2004. Unfortunately, an inventory (1676) of Heneage Finch’s London home, Kensington House, does not itemise any paintings: ROLLR, DG7/Inv. 2.

15 Both paintings were displayed together as a pair in the recent Tate Britain exhibition British Baroque: Power and Illusion: Bachelor 2020, p. 66.

16 The current owner, A.W.M. Christie-Miller, informed me (correspondence of 31 July 2003) that his father had purchased A Young Man Reading in a Courtyard at auction in 1953, ‘to match up with the other picture’, A Boy Chasing a Bird, which had been in the family’s possession for some time, probably ‘acquired in the mid/late 19th century’.

17 Latham/Matthews 1971-1983, vol. 9, p. 352.

18 Gloucestershire Archives (Heritage Hub), Gloucester, D1799/C2. Povey’s claims about Williams’ interests seem to have been true. In July 1679, he imported boxes of pictures, hangings, marble heads and furniture from Livorno in Tuscany: Shaw 1913, p. 160-161.

19 Roding/Stapel 2004.

20 Almost half the households assessed for the hearth tax in St. Margaret’s in 1664 were deemed exempt because of extreme poverty: Boulton 2000, p. 209.

21 I am grateful to Dr. Tony Trowles, Librarian of Westminister Abbey, for providing information on how Van Hoogstraten’s painting deviates from the actual appearance of the church in the mid 17th century.

22 A portrait of Elizabeth Harvey, Lady Finch, by Peter Lely was sold at Sotheby’s (London (England)) 23-11-2006, no.26.

23 City of Westminster Archives Centre, E47: ‘Of the Rt. Hon[oura]able Sr. Heneage Finch his Ma[jes]ties solicitor gen[era]l of his benevolence 40:0:0’.

24 Lysons 1813, p. 626.

25 Harvey 1993, p. 24-25.

26 Archer 2002, p. 231. Merritt 2005, p. 307.

27 Boulton 1997.

28 Between 1643 and 1645, the Abbey had been systematically ‘cleansed’ of many religious pictures, sculptures and stained-glass windows. See Spraggon 2003, p. 73-93.

29 In the mid 19th century, there was an iron poor box placed against a pillar in the south transept and inscribed with the same words (‘Blessed is he that considereth the poor’) as the plaque in Van Hoogstraten’s painting: Cunningham 1842, p. 84.