4.1 Samuel van Hoogstraten in London

Documentary evidence for Van Hoogstraten’s stay in England is largely confined to two letters he wrote from London to his Dordrecht friend Willem van Blijenbergh (1632-1696), a grain merchant who published on philosophy and theology, and scattered references throughout his treatise of 1678.1 According to the first letter of 2 August 1662, he had already been in London for almost three months, which would mean that he arrived in the city in June.2 The missive, which was written on Van Hoogstraten’s 35th birthday, is full of alienation; he bemoaned his lack of companions, particularly those with literary interests, and was dismayed at the religious tensions of the time, having witnessed a skirmish between soldiers and a group of Baptists. He had attended a service at the Dutch Church in Austin Friars, but neither he nor his wife became members of this congregation despite receiving an attestation from Dordrecht. Significantly, he was monitoring the movement of Charles II and his court, whose imminent return from Hampton Court to Whitehall [4] was anticipated. Van Hoogstraten concluded by telling his friend that ‘… since I now use my brushes more than my pen, I hope your excellency will hear of good success in time’.

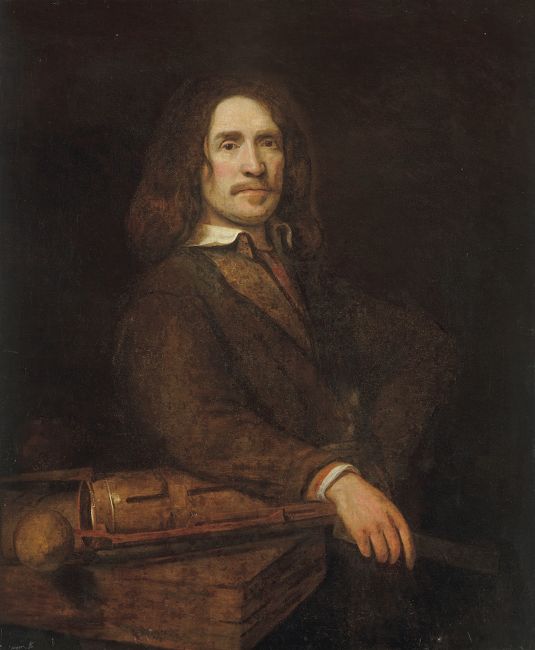

The second letter to Van Blijenbergh, sent in September of the following year, was less informative. Van Hoogstraten still complained that ‘his mind is drunk with poetry, but ink and pen are currently banned’ and that he is ‘forced to follow nature with paints’.3 He mentioned a mutual friend, ‘Mr. Sonneman’, who was also in London. This was Herman Sonneman, a collaborator of the famous gunmaker and engineer, Caspar Kalthoff (1606-1664), who ran a centre of experimentation in Vauxhall, south of the Thames.4 In 1657 Sonneman had provided the city of Nijmegen with a water pump made by Kalthoff, which failed to operate properly.5 From the German city of Solingen, Kalthoff was resident in Dordrecht during the Interregnum and returned to London in around 1660. The ‘Vauxhall Operatory’, as it was called, was established by Charles I (1600-1649) in 1629 and revived by Edward Somerset (1601-1667), 2nd Marquess of Worcester, after the Restoration.6 It brought together inventors of various kinds and consisted of firing ranges, workshops, foundries, and living space. Kalthoff produced repeating guns and steam-driven hydraulic pumps and was expert at grinding lenses for microscopes and telescopes.7 Van Hoogstraten probably painted his portrait in 1650 [5], with one of his inventions. In the Inleyding, he called Kalthoff a ‘seeker of perpetual motion’ and compared some of the light-hearted activities of the Vauxhall group to the wine-fuelled initiation rites of the Roman bentvueghels.8 In another passage he refers to a camera obscura that he had seen ‘in London near the river… hundreds of boats with people, and the entire river, landscape and the sky, on a wall, and everything capable of movement was moving’.9 Given its riverside location, this optical device may well have been set up in a room at the Vauxhall Operatory.

Van Hoogstraten did not live continuously in London between 1662 and November 1667, when he is first documented in The Hague, his place of residence for the next four years. We know that in August 1665, he was in Dordrecht, where he witnessed a notarial act.10 This was the year of the Great Plague, when London lost approximately 15% of its population, and the death rates were highest during the summer months. Privileged Londoners fled the city; among the exodus were patrons like Thomas Povey (1613/14-c. 1705), who went to live in his country villa near Brentford in Middlesex and wrote in October that ‘death is now become so familiar and the people so insensible of danger that they look upon such as provide for the public safetie as tyrants and oppressors’.11

The date of Van Hoogstraten’s return to England is unknown, but he had certainly returned by September 1666 when he witnessed the second catastrophe to visit the city in successive years: the Great Fire. He initially misjudged its seriousness, confusing ‘reddish smoke’ for billowing clouds when the light in his room in ‘Wijtstriet’ suddenly turned ‘red and glowing’. 12 The likely location, where he could watch the fire develop from a safe distance, was White Street in Southwark, south of the river, in the parish of St. George. This unassuming street was briefly described by John Strype (1643-1747) in his 1720 survey of London.13 Although Southwark had been inhabited by Dutch and Flemish textile workers, brewers, glassmakers and potters from the 16th century, it was less affluent and some distance from the fashionable districts. However, property was cheaper to rent here, and Van Hoogstraten may have needed a larger workspace to accommodate his sizeable architectural paintings. Most Dutch artists lived in the burgeoning west end, in Convent Garden and the Strand, and this geographical clustering aided the exchange of ideas, materials and contacts.14

There is some suggestion that Van Hoogstraten may have painted a sign for a tavern called The Rose, which was located in Poultry, a street connecting Cheapside and Cornhill and the centre of the poultry trade in the City. According to the anonymous author of a pamphlet published in 1852, a fragment of an account book had survived the Great Fire of London in 1666, when the tavern perished, which recorded a payment to Van Hoogstraten:

Pd. To Hoggestreete, the Duche Paynter, for ye Picture of a Rose, wth a Standing-bowle and Glasses, for a Signe, xxli, besides Diners and Drinkings. Also for a large Table of Walnut-tree, for a Frame; and for Iron-worke and Hanging the Picture, vli.20

Since the document is untraced and undated, it is impossible to confirm its authenticity. However, there is a specificity about the quoted words and there is no other known Dutch painter who worked in London, other than Van Hoogstraten, whose name approached ‘Hoggestreete’. While painting a sign might seem ignominious for an artist of Van Hoogstraten’s lofty aspirations, £20 was a significant sum.15

4

Hendrick Danckerts

Palace of Whitehall from Saint James’s Park, c. 1674-1675

London (England), Government Art Collection, inv./cat.nr. 12211

5

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Portrait of a man, dated 1650

Whereabouts unknown

Notes

1 On Van Blijenbergh: Van Bunge 2003, vol. 1, p. 111-113.

2 Roscam Abbing 1993, p. 59-60, no. 71.

3 Roscam Abbing 1993, p. 61-63, no. 74.

4 Sonneman was said to be living with Kalthoff, when he registered as a member of the Dutch Church in Austin Friars in April 1661 (London Metropolitan Archives, Dutch Church, Austin Friars, CLC/180/MS07402/09). Roscam Abbing erroneously transcribed his name as ‘Hendrik’. In 1663 Kalthoff and Sonneman were listed together among the debtors of the estate of Geertruyt Hoogers, deceased wife of the shoemaker, Cornelis Francken, for ‘shoes sent to England’ (Regionaal Archief Dordrecht, no. 20.195, 7 July 1663, fol. 611v.).

5 Van Schevichaven 1898-1904, vol. 1, p. 144-145.

6 On the Vauxhall research complex: Keller 2023, p. 233-238

7 Kalthoff provided the brothers Constantijn (1628-97) and Christiaan (1629-95) Huygens with knowledge and materials on how to grind lenses, which Christiaan used in the making of a telescope. See Van Helden/Van Gent 1999, p. 70.

8 Brusati 2021, p. 245.

9 Brusati 2021, p. 295.

10 Roscam Abbing 1993, p. 63-64, no. 76.

11 The National Archives, Kew (TNA), SP 29/134, T. Povey to Williamson, 5 October 1665.

12 Brusati 2021, p. 296-297.

13 Strype 1720, vol. 2, p. 30.

14 It is not impossible that Wijtstriet was a distortion or abbreviation of a place name in this area such as Wych Street or Whitecross Street. Some smaller streets could be alternatively called White Alley or White Street, such as one in Cripplegate Ward Without, close to Moorfields in the City of London. However, there is no evidence that any of these places were called White Street before the publication of Rocque’s map of London in 1746. See Harben 1918, p. 31.

15 London 1852, p. 4. The pamphlet was published on the reopening of the King’s Head Tavern. The writer tells us that a portrait of Charles II was subsequently added to ‘Hoogestreete’s’ sign. However, there are a lot of confusions in this text. The Rose was not the predecessor of the King’s Head and its proprietor in c.1651-66 was Thomas Dyott (or Dyose) not William King. In fact, the King’s Head tavern only came into existence in the mid 18th century. The most reliable account ofho the tangled history of the Poultry taverns is given by Bryant Lillywhite in his unpublished notes on London signs (Guildhall Library, London, SL 86:1, vol. 14, no. 12544).

16 Van Hoogstraten was not averse to accepting ‘lesser’ commissions. In 1678, the year of his death, for example, he was paid by the Dordrecht city government for making copies of two portraits of the stadholders: Roscam Abbing 1993, p. 77, no. 127.