2.3 Professional Relations between the Stone and De Keyser Families

Hendrick de Keyser had four sons who followed him into his profession, or one closely related to it. The eldest was Pieter de Keyser (c. 1595-1676) who was an architect,1 followed about a year later by Thomas (1596/97-1667) who was a portrait painter and stone mason,2 Willem (1603-1678 or later) who was a sculptor and architect3 and Hendrick II (1612/13-1665) who was a sculptor and mason.4 All of them had contact with the Stone family, either direct or indirect. A letter from Thomas, dated December 1639, survives, addressed to Nicholas and Mary in London. ‘Esteemed and very discreet brother and sister Stone’, it begins, ‘you will by this understand that we are all in good health and heartily hope for yours’. There follows a mixture of family news and business transactions with a financial reckoning for goods sent and received, including a beaver hat sent from London and a parrot cage from Amsterdam. A particularly interesting entry is for ‘2 frames for your son’s account’ which the De Keyser family had supplied.5 The son must have been Nicholas and Mary’s eldest son Henry Stone (1616-1653) who became a painter and sculptor,6 and the frames were presumably for his pictures. Henry had an elder sister, Maria who died young7 and two brothers, John (1620-1667) and Nicholas II (1618-1647) who followed their father and became sculptors, John being also a master mason.8 This meant that the second generation of the Stone family was almost a mirror image of the second generation of the De Keyser family with one daughter, a son who became a painter and other sons who took after their father as sculptors.

The De Keyser brothers and sister were roughly a generation older than their English cousins. Two of them, Willem and Hendrick the Younger, spent time in England and married English women. The transactions between the two families were by no means limited to picture frames and domestic goods. A series of memoranda in the Stone Account Book dating from June 1632 to January 1635 includes a note of receipt for a payment from Pieter de Keyser for four blocks of English alabaster, followed by a payment to a Dutch sea captain for a thousand black marble paving stones.9 English alabaster was a valuable export to the Netherlands as there was nothing comparable available locally. Likewise, black marble was a valuable import, considered to be of superior quality to its local equivalent which came mainly from Derbyshire, in the English Midlands. After the English Civil Wars broke out in 1642, the trade in stone with the Netherlands sustained the Stone family’s finances at a time when commissions for new sculpture and building work were hard to find.10

We know of no work by the elder Nicholas after the outbreak of war and it seems that he simply decided to retire. In 1647, with hostilities still in progress, the family suffered a triple disaster with the deaths of Nicholas I, Maria de Keyser and Nicholas II, all in the same year.11 They probably died in one of the epidemics which afflicted London from time to time. Henry survived them until 1653 and John until 1667.

This latter date, 1667, effectively marks the end of the Stone family as an artistic and architectural dynasty. The De Keyser family long outlasted them, although there is some uncertainty among historians as to who, precisely its later members were, how they were related and what they did. Willem de Keyser, the third son of Hendrick the Elder, is recorded in England in 1678 when he was admitted to the Masons’ Company of London as a ‘foreign member’.12 In 1681 a ‘Mr du Keizar’ was at work on a fountain at Kilkenny Castle for the Duke of Ormonde13 and it has been supposed that this, too was Willem or his son Hendrick Willemsz de Keyser.14

Artistic influences between the Stone and De Keyser workshops

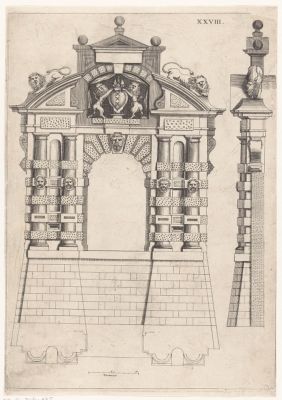

We know, then that the Stone and De Keyser families had a close personal and commercial relationship. The exact nature of their relationship as artists and architects, however, remains unresolved. It is quite clear that De Keyser’s work exerted a strong influence on the Elder Nicholas Stone and that this influence continued after De Keyser’s death. De Keyser’s most famous work of sculpture, the monument of William the Silent (Prince William I of Orange) in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft, commissioned by the States General of Holland in 1614 [8] can be seen reflected in one of Stone’s finest early works, the monument to Elizabeth, Lady Carey at Church Stowe in Northamptonshire, which dates from the end of the decade [9].15 The influence is apparent in the easy naturalism of the two effigies [10-11] which marks a break for Stone with the stiff and formal Elizabethan tradition. As far as architecture is concerned, we should note the impact of the treatise Architectura Moderna which was published in Amsterdam in 1631 and is illustrated largely by the work the De Keyser family. It contains an engraving of the Haarlemmerpoort in Amsterdam [12] and it has been pointed out that this was the major source for Stone’s main gateway to the Botanical Gardens in Oxford which was erected two years later to his own design [13]. 16

8

Hendrick de Keyser and Pieter de Keyser (I)

Funerary monument for Willem I 'the Silent' of Orange (1553-1584), 1614-1623

Delft, Nieuwe Kerk

9

Nicholas Stone (I)

Monument to Elizabeth, Lady Carey (1545/50-1630), c. 1618-1620

Church Stowe (Northamptonshire), St Michael's Church

Photo: the author

10

Nicholas Stone (I)

Monument to Elizabeth, Lady Carey, 1618-c.1620

Church Stowe (Northamptonshire), St Michael's Church

Photo: the author

11

Hendrick and Pieter de Keyser

Monument to William the Silent, 1614-1623

Delft, Nieuwe Kerk

Photo: the author

12

after Hendrick de Keyser (I) published by Cornelis Danckerts (I)

The Haarlemmerpoort in Amsterdam (from: 'Architectura Moderna'), 1631

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-2016-335

13

Nicholas Stone (I)

Main gateway to Oxford Botanical Gardens, 1632-1633

Oxford (England), Oxford Botanical Gardens

Notes

1 On his career: Ottenheym/Rosenberg/Smit 2008, p. 24. The authors mistakenly give his date of death as 1664.

2 On his career: Ottenheym/Rosenberg/Smit 2008, p. 25-26.

3 On his career: Ottenheym/Rosenberg/Smit 2008, p. 26-27, Colvin 2008, p.308 and Loeber 1981, p. 45-46.

4 On his career: Ottenheym/Rosenberg/Smit 2008, p. 27 and Roscoe/Hardy/Sullivan 2009, p. 356.

5 Spiers 1918-1919, p. 116-117. The letter was written in Dutch and is quoted here in the translation published by Spiers.

6 On his career: White 1999, p. 113-115.

7 Spiers 1918-1919, p. 20.

8 On the career of John Stone: White 1999, p. 115-118 and Colvin 2008, p. 989-990. On the career of Nicholas Stone II: White 1999, p. 138-139.

9 Spiers 1918-1919, p. 93-94. The last of these transactions is dated 1634 in the Account Book, according to the Old Style calendar which was still in use in England at that time.

10 Transactions of this kind in 1646-1647 are recorded in the foreign sketchbook of Nicholas Stone the Younger (Spiers 1918-1919, p. 25; White 1999, p. 138) The sketchbook is preserved in the Sir John Soane Museum in London, along with the Notebook and Account Book of Nicholas Stone the Elder.

11 Spiers 1918-1919, p. 12-13.

12 Colvin 2008, p. 308.

13 Costello 2016, p. 150-151.

14 Loeber 1981, p. 45-46.

15 White 1992, p. 43; White 1999, p. 120.

16 Ottenheym and De Jonge 2013, p. 122.