14.5 The Beauties of the Dutch School : Artists as Experts

As can be seen from the presence of modern Dutch painting in the British art world, the old masters were never far away; both in the choice of style and subject and in the interest of the buying public. Next to painting itself, the popularity of the Dutch old masters in Britain also offered other work opportunities. Knowledge of the old masters and their home country proved valuable in a market where the demand was high, and the offer enormous. It asked for expertise, preservation work and related publications.

For that reason, Cornelis Apostool (1762-1844) worked on a series of engravings after the Dutch old masters, for a booklet published in 1793: The Beauties of the Dutch School: selected from interesting pictures of admired landscape painters [15]. Following his drawing teacher Hendrik Meijer to the British capital, Apostool had been working in London for some time as an engraver, specialising in aquatints.1 In 1790, he had provided the aquatints for Samuel Ireland (1744-1800) in his A Picturesque Tour through Holland, Brabant, and Part of France.

‘Fearful of his ability to render justice to the views, and aware of the superior beauty and softness of the aqua-tints over the hard effect of etching, he called in the assistance of an ingenious artist, Mr. Cornelius Apostool, from Amsterdam; whose care in the execution of plates, and the close attention to the drawings, as well as professional skill, entitle him to this notice and tribute’,

so Ireland explained in the preface.2 For The Beauties of the Dutch School, Apostool executed 14 engravings. All but one were published in November 1792. The last one, after Cornelis Gerritsz. Decker (1615-1678), was published May 1793. The book was a coproduction with an anonymous author and compiled 'to convey a general idea of the works of the Dutch School’.3 The engravings were prefaced by an introductory text on the artist and his work. The writer also provided his readers with information on the position of the artist in the market and the approximate prices that were paid for his works. It can be viewed as publicity material and a guidebook or manual for collectors. Although the author remains anonymous, the address given, ‘no. 50, Leicester Square’, suggests the possible involvement of one of the principal London dealers in old master paintings, the auctioneer John Greenwood (1727-1792), since he resided at this address.4 Indeed, the writer mentions several prestigious sales throughout the book, presenting himself as an experienced and knowledgeable figure in the art market. In his preface, he explains how he took great care in the selection of the artists, their most characteristic works and the accuracy of the prints, aware of maintaining the exact 'touch, manner and pencilling' of the original artworks. He was therefore grateful to the Dutch printmaker Apostool 'for the faithful and accurate representation of the originals’.5 However, if it was indeed Greenwood, who was behind the book, the auctioneer was not present for the final publication, as he passed away in September 1792.

15

Cornelis Apostool after Jan van Goyen

View of the ramparts of Utrecht with Plompetoren (mirror image), 1792

Chicago (Illinois), Smart Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1976.145.251

15a

Jan van Goyen

View of the ramparts of Utrecht with Plompetoren, dated 1647

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 64.65.1

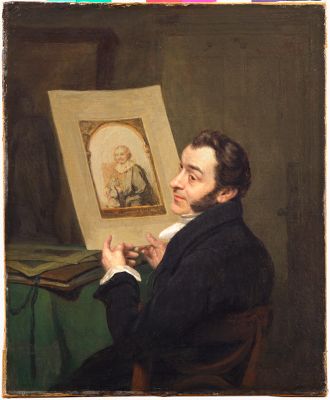

Like Apostool, Christiaan Josi (1768-1828) initially came to London as a printmaker. He arrived in London in 1791 on a scholarship to be trained as a stipple engraver. He returned to Amsterdam in 1796 and left printmaking behind to set up his own gallery as an art dealer in the Dutch capital. By the time he returned to London in 1818, Josi was an established art dealer, and one of the most important specialists in Dutch and Flemish prints and drawings, already selling works to Britain from Amsterdam.6 When Pieter Christoffel Wonder arrived in London, Josi showed him around and a portrait dated 1826 now kept at Fondation Custodia in Paris is most likely of Josi by Wonder [16]. An art dealer is sitting at a table with works on paper. The model is holding up a print, presumably a hand-coloured etching after what was then considered a self- portrait by Rembrandt (1606-1669) [17].7 The print was executed by Josi himself and included in the elaborate album of prints he had published in London in 1821: Collection d'imitations de dessins d'après les principaux maitres Hollandais et Flamands. The book was an initiative of printmaker and dealer Cornelis Ploos van Amstel (1726-1798) and had been in Josi's mind to finish for a long time, before finally venturing on the project after he had settled again in London. It consisted of 100 etchings after drawings by the Dutch and Flemish old masters, accompanied with detailed information on the artists. Josi presented himself as an expert in the field: ‘There are few galleries, libraries and cabinets in Holland, England and France that I have not examined’, he explains.8 He continues by describing the popularity of the old masters and the rising prices of their paintings and prints. Furthermore, he stresses that, although much had been written about Dutch painting and printmaking, a treatise on Dutch and Flemish drawing was still missing, leaving many foreigners in the dark about this aspect of the fine arts. It was for this reason that Josi decided to publish his album in French, the international ‘lingua franca', even though he was less trained in French than English. Undoubtedly, there was a commercial aspect to the publication, which can be viewed as a celebration of Dutch and Flemish drawing, ‘not less interesting than painting and prints of this school and nowadays forming the major part of the collections in Holland, particularly in Amsterdam’.9

Another London publication with Dutch origins is worth mentioning. In 1832, Abraham Bruiningh van Worrell, discussed in section 4, published a book entitled Van Worrell’s Tableau of the Dutch and Flemish painters of the old school. His reasons for writing the book were evident:

'It might be considered presumption in a Foreigner to attempt the production of a literary work in the English language; but the very circumstance of my being a Dutchman, and myself an artist, may perhaps be deemed a sufficient excuse for my venturing on the publication of the following Tableau of Dutch and Flemish painters of the old school, as my familiarity with the names of my own countrymen and the nature and bent of my studies, have, I trust, in some measure, qualified me for the undertaking’.10

‘It may be asked’, Van Worrell continues, 'what object have I in view in writing this Tableau: this is my answer – There are many of the nobility and gentry, who possess the finest galleries and collections of pictures, by whom I have oftentimes been employed to restore works of the old masters, and frequently found names given to pictures which I knew to be incorrect. […] How very necessary it is then that those who possess galleries or collections of pictures, or those who are endeavouring to obtain them, should be well acquainted, and sure whose work it is […]'.11

The artist's Dutch origins, and thereby claimed expertise, justified his venture into a publication that would function as a useful manual for collectors and a warning always to keep a critical eye on the large amount of Dutch art that circulated on the market. In between the lines, Van Worrell also gave away two more of his professions. He had delivered work as a copyist and was frequently asked for restoration work. Likewise, Hendrik Willem Schweickhardt was asked to restore paintings as can be learned from the account book, discussed earlier.12

It must be added that Van Worrell’s publication not only reached out to collectors. A copy of the book is kept at the Royal Academy of Arts, from the collection of the British painter Sir Augustus Wall Callcott (1779-1844).13 Callcott, like many British painters at the time, admired the Dutch old masters, Cuyp particularly [18].14 Following the old masters, was not only a Dutch affair.

16

Pieter Christoffel Wonder

Portrait of a man, probably Christiaan Josi (1768-1796), dated 1826

Paris, Fondation Custodia - Collection Frits Lugt, inv./cat.nr. 1975-S.1

17

Christiaan Josi after Rembrandt published by Cornelis Ploos van Amstel

Portrait of Willem van der Pluym (ca. 1595-1675), published in 1821

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-47.806

18

Augustus Wall Callcott (Sir)

Meadow with herd in the background the city of Dordrecht, dated 1841

London (England), Victoria and Albert Museum, inv./cat.nr. FA 11

Notes

1 Jonker 1977. Several of these prints are kept at the British Museum.

2 Ireland 1790, vol. 1, p. xi-xii.

3 Apostool 1793.

4 Venemans 2010, p. 277.

5 Apostool 1793, n.p.

6 In 1810, Josi sold the prestigious collection of prints by Rembrandt from Cornelis Ploos van Amstel to the Earl of Aylesford. Frits Lugt, Les Marques de Collections de Dessin et d’Estampes (http://www.marquesdecollections.fr/detail.cfm/marque/6248), accessed 10 December 2023.

7 See Craft-Giepmans et al. 2012, cat. 73.

8 Josi 1821, p. xiv. ‘Il est peu de galeries, de bibliothèque ou de cabinets en Hollande, en Angleterre et en France que je n’aie examiné à loisir’.

9 Josi 1821, p. i. ‘non moins intéressante que celle des tableaux et des estampes de cette école, forme aujourd’hui la principale partie des collections en Holland, et plus particulièrement à Amsterdam’.

10 Van Worrell 1832, p. v.

11 Van Worrell 1832, p. vi-viii.

12 Sluijter 1975, p. 196-208.

13 Royal Academy of Arts, London, inv.nr. 07/34.

14 On the influence of Cuyp on Callcott: Paarlberg et al. 2021. For a more general investigation of the influence of Dutch painting on British landscape painting: Bachrach 1970.