13.1 English Admirers and Followers

'Whom no Age has equall'd in Ship-painting'

Willem van de Velde the Younger was widely appreciated as a painter in 18th-century England can be seen from testimonies by critics. Here are some telling examples. Already during his lifetime and shortly after his death, there was praise. Bainbrigg Buckeridge (1668-1733) [4] summarised this concisely in his Essay towards an English-School of Painters (1706) when describing the work of the artist's father: 'He [Willem van de Velde the Elder, RD] was the Father of a living Master Whom no Age has equall'd in Ship-painting and this we owe to his Father's Instructions'.1 Shortly afterwards, George Vertue (1684-1756) [5] the renowned antiquarian and chronicler of the arts went even further in his assessment: 'William Vandevelde, the son, was the greatest man that has appeared in this branch of painting; the palm is not less disputed with Raphael for history, than with Vandevelde for sea-pieces: Annibal Caracci and Mr. Scott [the marine painter Samuel Scott, RD] have not surpassed those chieftains.'2 Coming to a similar judgement, later in the century, Matthew Pilkington (1701-1774), author of a painters’ lexicon, later known as Pilkington's Dictionary, stated: '... whether we consider the beauty of his design; the correctness of his drawing; the graceful forms and positions of his vessels; the elegance of his disposition; the lightness of his clouds; the clearness and variety of his serene skies, as well as the gloomy horror of those that are stormy [...] they are all executed with equal nature, judgement, and genius...'.3 The verdict is certainly positive, but somewhat reserved: neat paintings, which stand out above all for the correctness and precision with which they are executed. Perhaps this explains why works by Van de Velde rarely seem to have been considered the most important pieces to collect and thus did not fetch the very highest prices in the art trade, especially compared to masters such as Titian, Rubens and Rembrandt.

Among artists, at least in the maritime field, Van de Velde did count as the very highest level one could reach. Until the arrival of the Van de Veldes maritime art was a new phenomenon in England. Marine painting as a specific genre with specialised practitioners as in the Dutch Republic, did not yet exist there. The Van de Velde's actually stepped into a gap in the market, partly with the support of the two kings from the house of Stuart, Charles II and his brother James II. Both, and James in particular, had a personal interest in the navy. James even held the position of Lord High Admiral for some years while he was still Duke of York. In that capacity, he was even present at the Sea Battle of Solebay against the Dutch in 1672.

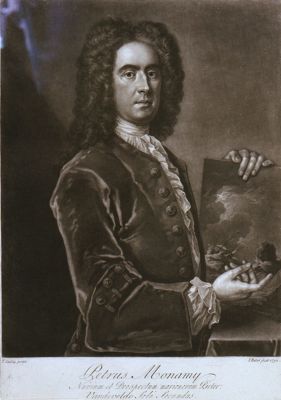

James’ successor, William III of Orange, the Dutch stadtholder-king, had no great interest in either the war fleet or naval painting, and in 1688 the Van de Veldes' honorary role as court painters came to an end.4 It also meant that these marine painters had to look for new clients, among high-ranking naval officers, but also among wealthy citizens who wished to have their homes decorated. London's urban expansion and the growth of the maritime sector in the economy worked strongly in their favour. From then on, the demand for marine paintings inspired many other artists in England. A whole series of English marine painters can be identified who emulated, or simply imitated, Van de Velde's compositions and style. They called it 'painting in Vandervelt's taste'. Significantly, one of these imitators, Peter Monamy (1681-1749), had a Latin inscription placed under his etched portrait stating that he was 'Vandeveldo soli secundus' (second only to Van de Velde) as a marine painter [6]. Van de Velde's example was followed by painters such as Monamy, Samuel Scott (1702-1772) and Charles Brooking (1723-1759), to name just a few. One of the painting types for which they received commissions were ship’s portraits, if desired in the form of a group portrait with other vessels, a new type of painting [7-8]. Van de Velde taught them that the best way to depict a large decorated ship was to paint it three-quarters stern view, starboard or port. In this way, the most ornate part of the ship, the stern, was most clearly visible.5 His calm seascapes and coastal scenes and ships in stormy weather also inspired not only Turner, but also many early marine painters in England.6

4

Michaël Dahl (I)

Portrait of Bainbrigg Buckeridge (1668-1733), dated 1696

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG 6521

5

George Vertue

Self portrait, dated 1741

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG 4876

6

John Faber (II) after Thomas Stubly

Portrait of Peter Monamy (1681-1749)

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. PAF3374

7

Peter Monamy

English fleet coming to anchor, late 1720s

Greenwich, National Maritime Museum (Greenwich), inv./cat.nr. BHC1005

8

Willem van de Velde (II)

The English warship Britannia coming to anchor, c. 1697

Private collection

As is well known, both Van de Veldes made a huge number of drawings, of ships, sea battles and all sorts of details. The Maritime Museum in Greenwich has no less than 1450 of them, and the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam owns almost 600. Originally these drawings served primarily as documentation for the Van de Velde studio. Clients could look at them when discussing a commission, and the artists had them at hand when filling in details. Interestingly and significantly, after the death of both Van de Veldes, British marine painters collected these drawings in turn. Samuel Scott, for example, owned some 500 Van de Velde drawings at the time of his death in 1772. Turner also had dozens.7