11.4 Worlidge’s Approach to and Interpretation of Rembrandt’s Tronies

Worlidge had various opportunities to study works by Rembrandt, as he had a close network of other artists, collectors and patrons. Through Edward Astley‘s (1729-1802) purchase in 1756 of Arthur Pond’s former collection of prints, Worlidge gained access to first-class works by Rembrandt. Astley was his patron, whom he portrayed in the same way as Rembrandt portrayed his patron, Jan Six. [27].1 Worlidge studied Rembrandt’s work very intensively. He adopted a technique between acid bite and dry point etching that imitated Rembrandt’s etching manner very closely [28-31].2 He became so good at imitating Rembrandt’s technique that he advertised his own work by claiming that he could etch any head ‘in the manner of Rembrandt’.3

The ways in which Worlidge used Rembrandt’s works for his own tronies varied from imitation and copying to selective adaptation of individual elements of an image. However, Worlidge did not simply copy Rembrandt’s etchings; he also used Rembrandt’s prints as a source or a basis for developing his own works.

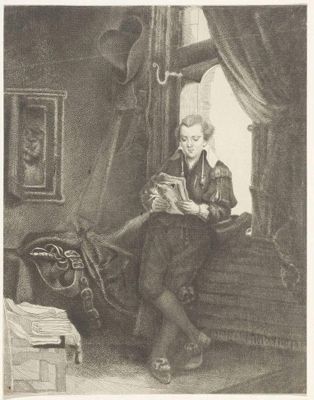

27

Thomas Worlidge after Rembrandt

Portrait of Edward Astley (1729-1802) as Jan Six, dated 1762

Amsterdam, Six Stichting

28

Thomas Worlidge after Rembrandt

Portrait of Rembrandt in a cap and scarf, c. 1758

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1852,0214.222

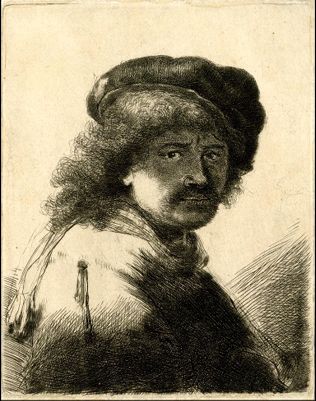

29

Rembrandt

Self-portrait in a cap and scarf with the face dark, dated 1633

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-281

30

Thomas Worlidge after Rembrandt

Beggar seated on a bank,

London (England), British Museum

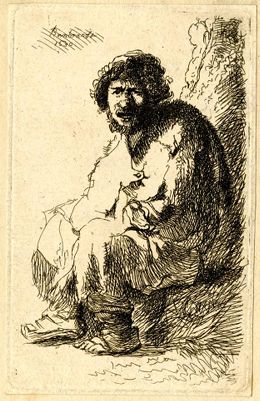

31

Rembrandt

Beggar seated on a bank,

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. F,5.126

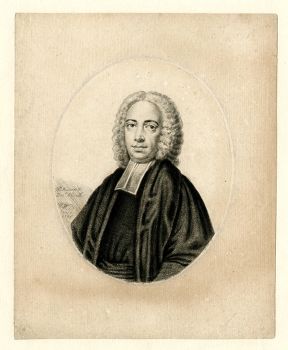

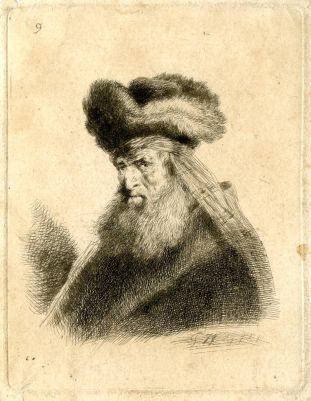

An example of Worlidge’s working method is the etching of Bust of an Unidentified Man [32], which he made in 1751, at the beginning of his intensive study of Rembrandt’s work. The 194 x 144 mm etching shows a middle-aged man turned sideways, his gaze fixed past the viewer. In addition to his heavy fur-trimmed coat, the man’s headdress is particularly striking. He is wearing a hat with wide fur brims, which are folded upwards. Underneath, he wears a striped headscarf, the loose ends of which drape over his shoulders. The garments were partly borrowed from Rembrandt’s repertoire. They were modified accordingly, so that Rembrandt’s model can be traced, but no definite identification can be made. For example, we find a similar coat in Rembrandt’s Man with a tight cap [33] and a similar form of headgear in Rembrandt’s Bearded Old Man with a high fur cap [34]. Worlidge was certainly aware of these two tronies, as he made copies of the etchings [35]. In addition, Worlidge restricted the light to a small part of the face, contributing to the dramatic chiaroscuro for which Rembrandt was particularly praised by Worlidge’s contemporaries. Worlidge imitated the short, wavy lines with which Rembrandt often drew the eyes and paid particular attention to the construction of different textures. In other areas of the face, however, Worlidge worked with strong outlines and created shadows with an almost linear grid structure. These are characteristic of classical portrait engraving, which Worlidge also used in some of his portrait prints, for example in the portrait of Reverend John Nicoll [36]. The analysis shows that Worlidge combined technical elements adapted from Rembrandt’s etchings with typical elements of printmaking.

32

Thomas Worlidge

Portrait of a man in oriental dress, dated 1751

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1907,0724.5

33

Rembrandt

Man wearing a close cap (the artist's father?), dated 1630

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

34

Rembrandt

Bearded old man n a high fur cap, with eyes closed, c. 1635

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-586

35

possibly Thomas Worlidge Rembrandt

Man wearing a close cap

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-12.391

36

Thomas Worlidge

Portrait of Reverend John Nicoll, Headmaster of Westminster School, dated 1756

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1875,0508.640

The Bust of an old Man [37] is another example of Worlidge’s intensive study of the popular so-called ‘oriental’ tronies that Rembrandt produced in print, painting and drawing. The etching, measuring 127 x 98 mm, was made by Worlidge in 1751, as the signature indicates. The print shows strong physiognomic parallels with Rembrandt’s so-called Third Oriental Head, which Rembrandt copied from a work by Jan Lievens [38-39]. The similarities are best seen in the distinctive nose, long beard and prominent cheekbones, which remind the viewer of the old man in Rembrandt’s tronie. Another feature that recalls Rembrandt’s work is the long headscarf that falls over the man’s shoulders. The resemblance to the model is obvious, but is by no means intended as a direct copy. Moreover, Worlidge seems to have been inspired by Rembrandt’s work, and perhaps even Lievens’s, to create a new image.

37

Thomas Worlidge

Tronie of an old man with a beard and fur hat, dated 1751

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1925,0511.177

38

Rembrandt after Jan Lievens

Bust of an oriental man with a turban, dated 1635

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-583

39

Jan Lievens

Bust of an Oriental with beard and turban, c. 1630-1632

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-12.553

In 1759, Worlidge etched another Bust of a Man [40], a clear reference to Rembrandt’s so-called Second Oriental Head, which he also copied from Lievens [41-42]. The work depicts a middle-aged man whose features, unlike in Rembrandt’s own etching, are reminiscent of Rembrandt’s physiognomy. Worlidge’s tronie is not shown in profile but facing the viewer. The headdress and fur coat are the most obvious signs of an intense preoccupation with Rembrandt’s tronie, as the scarf tied tightly around the man’s head pushes up the fur trim underneath. The scarf or lace cravat can be seen as a disruptive element in the overall Rembrandt-inspired tronie. It is more associated with contemporary English menswear, as in the portrait of King George III of the United Kingdom (1738-1820) [43]. Compared with the Bust of a Man, Worlidge’s work shows that he had developed technically and found new ways of expressing himself apart from the classical approach he used in 1751. For example, he moved away from the straight grid lines that he used to define bodies and shapes. Instead, he traced his etching lines loosely several times, pausing in between and picking up the line a little further, resulting in a dynamic approach to the body. This process is best seen in the first state of the Bust of a Man [44], where he sketched the head and face first. The rest of the body is indicated only by contouring lines. The example underlines the fact that Worlidge was rapidly developing his etching techniques.

40

Thomas Worlidge

Tronie of a man in oriental dress, dated 1759

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1907,0724.4

41

Jan Lievens published by Frans van den Wijngaerde

Bust of an old man in orienral dress in profile, c. 1630-1632

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-12.558

42

studio of Rembrandt and Rembrandt after Jan Lievens

The second oriental head, c. 1635

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. KG 03857

The examples shown here represent only a fraction of Worlidge’s etchings. In many of his works, however, the technical boundaries between tronie and portrait are less clearly defined than in the etchings of Rembrandt which makes the categorization of the etchings more challenging. Whether the sitters were anonymous models, commissioned portraits, or perhaps costume portraits, was essentially irrelevant though. For the sale of the works, the clear identification of the model was secondary; rather, they represented Worlidge’s ability to depict people ‘in the manner of Rembrandt’. The absence of names, portrait-like features, the use of seemingly specific Rembrandt tronie clothing or the creation of images that bear striking resemblance to Rembrandt himself are all used strategically. Worlidge referenced garments from Rembrandt’s repertoire, but altered them to suit his purpose, which was to combine historical pieces with contemporary ones. The connections to the original motif were left for the viewer to make. However, since Worlidge did not reference a specific Rembrandt print, but rather multiple ones, it remained difficult for viewers to identify the etching he was referencing, resulting in an ambiguous interpretation. This was a practice that Rembrandt had employed in his tronies as well. One can only imagine that this procedure would have led to lively and lengthy discussions among connoisseurs.

Worlidge echoed Rembrandt’s vivid approach to rendering characteristic, recognisable faces. He evoked a certain ambiguity between tronie and portrait that made his works so compelling to viewers. Together with the strong references to Rembrandt’s popular works, his etchings therefore appealed to a wide art market.

43

Thomas Worlidge or after Thomas Worlidge

Portrait of King George II (1683-1760), c. 1753

London (England), National Portrait Gallery, inv./cat.nr. NPG 256

44

Thomas Worlidge

Tronie of a man in oriental dress, 1759

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1925,0511.181

Notes

1 Yarker 2018, p. 87-88.

2 If one follows Gerson’s arguments, this only applies to the etchings Worlidge made after Rembrandt and not the paintings. Gerson 1942/1983, p. 445. Gerson 1970, p. 305.

3 Howard 2010, p. 42-43. In 1852, Nagler mentions in his encyclopedia of artists that Worlidge had etched some 140 works ‘in the manner of Rembrandt’: Nagler 1852, p 88. Charles Dack lists a total of 236 etchings by Worlidge, almost half of which are portraits or other depictions of the face: Dack 1907, p. 19-30.