11.3 The Tronies in Context

Emergence in the Netherlands in the 17th Century and Dissemination in England in the 18th Century

Worlidge etched several tronies. It is uncertain how many he actually produced as his oeuvre has not been fully identified and recorded to date. To understand Worlidge’s approach to the tronie, it is necessary to look more closely at Rembrandt’s work. In Rembrandt’s oeuvre, approximately 70-80 prints can be identified as tronies.1 Rembrandt developed the tronies, which are often called facial or character studies, mainly at the beginning of his career, together with his friend and colleague Jan Lievens (1607-1674).2 The tronies allowed the young artists to push the boundaries of motif, technique and style. Rembrandt and Lievens both produced two extensive tronie oeuvres, mainly in print, but also in drawing and painting, until they both went their separate ways in the early 1630s [14-17].

14

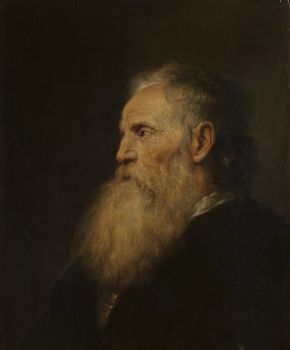

Rembrandt

Bust of an old man, dated 1632

Cambridge (Massachusetts), Fogg Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1930.191

15

Jan Lievens

Portrait of an old man, 1631-1632

Sint-Petersburg, Hermitage, inv./cat.nr. ГЭ-736

16

attributed to Rembrandt or attributed to Jan Lievens

Bust of an old man, c. 1626

Private collection

17

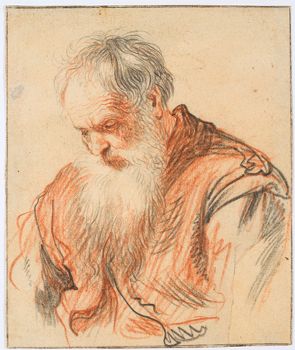

Rembrandt

Bust of an old bearded man, looking down, dated 1631

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-501

Rembrandt’s and Lievens’s tronies differ from portraits in that they were not meant to be representational in the sense of identification.3 Rather, tronies, as autonomous artworks, correspond to certain types of figures that appear, for example, in history paintings of Rembrandt [18] and Lievens. Formally, tronies can also be designed and technically executed much more freely than portraits [19]. As a result of their independence from the rules of the genre, the faces of tronies tend to be more expressive, which is why they are often described as ‘study-like’ [20].4 Special lighting, partial shadows and the removal of outline and structure characterise these works. At the same time, they serve as an experimental ground for the depiction of extravagant, often historicising costumes or people dressed in rags, unusual combinations of clothing, jewellery or weapons. Often, only one of these aspects is elaborated on, sometimes all of them, suggesting that the visualisation of different surface textures is one of the main purposes of tronies.

18

Rembrandt

Samson threatening his father in law, dated 163(5)

Berlin (city, Germany), Gemäldegalerie (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), inv./cat.nr. 802

19

Jan Lievens published by Jan Lievens

Portrait of the French lute player and composer Jacques Gaultier (fl. 1617-1652), 1632-1635

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-12.605

20

Rembrandt

Rembrandt's mother, 1628

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-747

It is noticeable that the models are often dressed in ‘orientalised’ fantasy fashions, with headscarves, turbans and other supposed attributes associated with the contemporary reception of what was then known as the ‘Orient’, which Worlidge later echoed in his own prints due to the popularity of so-called ‘turqueries’ around 1750 [21-22].5 In Rembrandt’s and Lieven’s work, the tronies as individual heads functioned primarily, but not exclusively, as printed business cards.6 On the basis of these mostly small and inexpensive prints, Lievens and Rembrandt were able to promote their signature style and signature motifs as a novelty on the art markets in order to attract buyers, but also, as specialised history painters of the time, future collectors for their larger biblical or mythological compositions.

When the printed tronies arrived in England, they contributed to an art market that was primarily concerned with portraiture. Portrait painting was the most popular genre in England, with the celebrated painters Hans Holbein II (1497/8-1543) and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) dominating the respective English courts they worked at with their portraits [23-24].7 Along with countless other portraitists, they shaped the tastes of the English aristocracy, who had little interest in history painting. Portraits hung in the country houses of the upper classes and for decades were seen as a manifestation of social status and identity but mainly of lineage.8 Hence, the craving for portraits was primarily linked to the person portrayed – a craving that tronies could not satisfy since the models always stayed anonymous. Instead, the tronie fulfilled another widespread desire in the 17th and 18th centuries, which was the precise study of the human face.9 Printed tronies played a key role in stimulating this interest since they provided viewers with the opportunity to scrutinize them in detail and compare several tronie prints with each other through the medium of print.

Aside from tronies being facial representations, a significant aspect of their appeal to the English audience was their distinctive nature as artworks by Rembrandt. For a considerable amount of time, Rembrandt's paintings were unavailable in England, resulting in the use of prints as substitutes. Tronies initially represented the most abundant Rembrandt prints as they were produced in large quantities during Rembrandt’s lifetime. Moreover, they were highly regarded from an early stage. This reflects in art theoretical writing from that time when, for example, John Evelyn already mentions Rembrandt’s prints, and especially some of the tronies, in high notes in his 1662 published Sculptura or the History and Art of Chalcography and Engraving in Copper. Evelyn states: 'To these we may add the incomparable Rembrandt, whose Etchings and gravings are of a particular spirit; especially The old Woman in the fur; The good Samaritan; The Angels appearing to the Shepherds; divers Landschapes and Heads from the life; St. Hierom, of which there is one very rarely graven with the burin; but, above all, his Ecce Homo; Descent from the Cross in large; Philip and the Eunuch, &c.'.10 Rembrandt's prints, specifically his tronies, received recognition for their unique approach to etching and the high quality associated with them, which made them attractive to buyers.

In using the Dutch tronies as a source of inspiration for his own tronies and portraits, Worlidge drew on a well-established tradition of facial representation in England and linked it to new cultural trends that had emerged in the art market.

21

Rembrandt

Bearded old man in a fur cap, with eyes closed, c. 1635

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-586

22

Thomas Worlidge

Portrait of a man in oriental dress, dated 1751

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1907,0724.5

23

Hans Holbein (II)

Portrait of a nobleman with a hawk, dated 1542

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 277

24

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Frances Devereux (1599-1674), Duchess of Somerset, c. 1636

Syon House (Hounslow), Alnwick Castle, private collection Ralph George Algernon (12th Duke of Northumberland) Percy

Notes

1 On Rembrandt’s prints: NHD Rembrandt 2013.

2 Dickey 2019, p. 37-39.

3 On the definition of ‘tronies’: Gottwald 2011, p. 9. Hirschfelder 2008, p. 38-41, p. 353. Hirschfelder 2014. Welkens 2023, p. 2-7.

4 Bauch 1960, p. 173-180. De Vries 1989, p. 191.

5 Travellers’ accounts and the objects they brought back from their travels were used to depict life and culture in the East. Fine fabrics and unusual objects found their way into portraits, testifying to exquisite taste, knowledge of other cultures and even superiority over them: Gibson-Wood 2002, p. 492. Pointon 1993, p. 147-148. Lemaire 2000, p. 54-57.

6 Hirschfelder describes the tronies in this context as "abbreviations" of a specific artistic style: Hirschfelder 2008, p. 342.

7 Gibson-Wood 2000, p. 9.

8 Pointon 1993, p. 13-14.

9 Hirschfelder 2014, p. 51-53.

10 Evelyn 1769, p. 78.