11.1 The Rise of Rembrandt’s Art in England around 1700

By the early 18th century, Rembrandt’s name was already known to a specific group of art lovers and collectors in England, but they had little knowledge of his work. The situation in England was not comparable to Rembrandt’s fame in France at the same time, where his art had been widely circulating since the early 1630s.1 In France, it was his prints in particular that helped to establish his reputation as an artist, and led to his paintings being included in the most prestigious collections. In England, however, only three paintings by Rembrandt are known to be in collections at the beginning of the 18th century.2

However, towards the conclusion of the 17th century, works from the lower segment of the Dutch art market were being imported to England in significant quantities. This was largely due to the ‘Glorious Revolution’ in 1688 and the relaxation of regulations surrounding the importation of paintings.3 The great masses of paintings that arrived in England were comparably inexpensive to the buyers and soon people started to decorate their homes with them.4 Also, knowledge of European high culture was based on the possession of paintings from continental Europe and, as Carol Gibson-Wood put it, ‘taken over as the political duty and privilege of the ruling class […]’, which led to a demand for high quality Dutch works.5 Rembrandt’s works were particularly sought after. By the 1720s, major paintings by Rembrandt were entering the English art market and being placed in the collections of the English aristocracy.6

As well as paintings, many of Rembrandt’s prints began to circulate in England. The first evidence of a larger collection of Rembrandt prints in England is the sale of Richard Maitland (1653-1695) in 1689.7 His collection of 10,000 sheets included around 420 works by and after Rembrandt. This is the first known sale of a collection of Rembrandt prints described as ‘complete’ by contemporary standards.8 A real economic upsurge in the collection of Rembrandt prints can be linked to the theoretical preoccupation with them.9

The involvement of Jonathan Richardson Senior (1667-1745) is generally regarded as the initial spark for the study of Rembrandt and the trade of his prints in England.10 Artist and art theorist Richardson, who owned a large collection of Rembrandt prints, repeatedly discussed Rembrandt’s work in the second edition of his widely known Theory of Painting, published in 1725.11 He singled out Rembrandt as one of the best painters to study the criterion of ‘variety’, which was part of his critical evaluation of works of art.12 With the aspect of ‘variety’ Richardson addressed a balanced representation of people in a painting, particularly in terms of diversity, such as age, gender and ethnicity. Surprisingly, Richardson chose the 100-Gilder print of Rembrandt to visualize his concept [3]. Usually, paintings – and not prints – illustrated theoretical ideas about art. Richardson’s Theory of Painting can therefore be seen as the beginning of the appreciation of Rembrandt’s prints in English art theory, which laid the intellectual foundations for collectors.

The theoretical discussion also led to an artistic approach to Rembrandt’s art, especially his prints, within the art community. Young artists began to study Rembrandt’s works, not only because they were stimulating from an artistic point of view, but also because they were beginning to set the standard for modern artistic taste, thereby attracting better commissions. In this context, one of the first important acquisitions, particularly for Thomas Worlidge, was made by the artist Arthur Pond (1701-1758). Pond bought a large number of first-class Rembrandt prints from Jacob Houbraken (1698-1780) around 1748. Fourteen years earlier, Houbraken had originally obtained the prints from Willem Six (1662-1733), the nephew of Jan Six (1618-1700) – Rembrandt’s Amsterdam patron and supporter [4].13 The Pond collection was offered on the English art market in 1750 and later Worlidge gained access to it. This is an example of how Rembrandt’s prints gradually entered the English art market.

Edmé Gersaint’s (1694-1750) Catalogue raisonné de toutes les pieces qui forment l’oeuvre de Rembrandt [5] marked a turning point in the collection of Rembrandt’s prints. It was the first attempt to bring the prints into order and to catalogue the numerous states of the prints in circulation. The catalogue was first published in France in 1751. A year later, in 1752, it was translated into English and published in London as A Catalogue and Description of the Etchings of Rembrandt Van-Rhyn [6-7].14 Gersaint was responding to a contemporary desire for order and an overview of Rembrandt’s printed oeuvre that would allow the exchange of expert opinions and the verification of authenticity by connoisseurs. The resulting debate was openly conducted by (self-appointed) print experts, who published new catalogues and indexes in which each of them claimed their authority, attributing prints to Rembrandt and (allegedly) discovering new states. Rare or even new states could be recorded and valued on a comparable basis.15 They also served as a tool for publicly representing the knowledge of connoisseurs.16 As a result, Rembrandt became one of the most discussed and collected artists of the time.

3

Rembrandt

Christ healing the sick (The Hundred Guilder Print), c. 1648

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1962-1

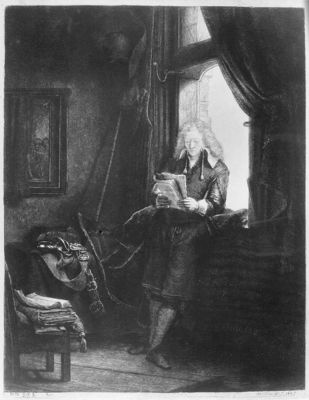

4

Rembrandt

Portrait of Jan Six (1618-1700), dated 1647

Whereabouts unknown

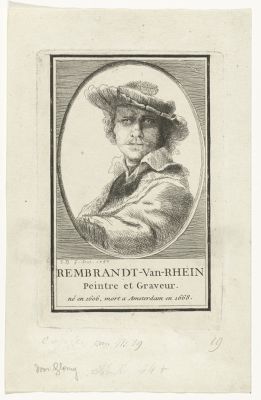

5

Jean-Baptiste Glomy after Rembrandt

Portrait of Rembrandt (1606-1669), dated 1750

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-12.288

6

after Jean-Baptiste Glomy after Rembrandt

Portrait of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), 1752 or shortly before

Whereabouts unknown

7

Rembrandt

Self portrait with Saskia, dated 1636

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-34

Notes

1 Seifert 2018, p. 22.

2 Seifert 2018, p. 26.

3 Gibson-Wood 2000, p. 16.

4 Gibson-Wood 2000, p. 16-17.

5 Gibson-Wood 2000, p. 17.

6 Seifert 2018, p. 26.

7 Seifert 2018, p. 21.

8 Seifert 2018, p. 21.

9 Joachimides 2011, p. 226.

10 Joachimides 2011, p. 225-226. Seifert 2018, p. 23. Yarker 2018, p. 84-85.

11 Richardson 1725. This is the 2nd edition of the essay. The first edition was published in 1715. Slive 1953, p. 153.

12 Richardson 1725, p. 66-68. Slive 1953, p. 150. Robinson 1981, p. 66.

13 D’Oench 1983, p. 67. Yarker 2018, p. 87.

14 Gersaint 1751. Gersaint 1752.

15 Dickey 2018, p. 69.

16 Smentek 2014, p. 115.