10.2 His Notes on Prints: Names and Monograms

William Cartwright left 13 double-sided pages of paper in his own handwriting, pasted into one album. The first 10 pages have 19 sides with an inventory of his paintings (fols. 1r-10r; fol. 10v has been left blank).1 The last 3 pages have 4 sides with transcripts of 161 names that Cartwright had found on prints (fols. 11r-12v, with as heading ‘Italian masters […]’) [4-7]. On the front side of the third and last page there are 28 monograms that he had also found on prints (fol. 13r, with as heading ‘Markes of ye Best prints’) [8]; on this page there are also seven more names, nos. 162-168. The last side (fol. 13v) has been left blank. This list was probably a draft, intended to be written up properly, ordered alphabetically.2

4

Cartwright's Notes on Prints, p. 1, Dulwich College Archive, MS XIV, fol. 11recto

5

Cartwright's Notes on Prints, p. 2, Dulwich Collge Archive, MS XIV, fol. 11verso

6

Cartwright's Notes on Prints, p. 3, Dulwich College Archive, MS XIV, fol. 12recto

7

Cartwright's Notes on Prints, p. 4, Dulwich College Archive, MS XIV, fol. 12 verso

The first question is: what kind of list is this? To start with, there is a clear difference between the inventory of paintings and the notes on prints. The information about the paintings is always stated more or less systematically by Cartwright and can also be considered complete. In the margin is the number of the painting, usually with the appraisal value that he gives it.3 He always starts his description of the paintings with the subject. He also states the size of the painting, and whether or not there is a frame around it and what the frame looks like [9]. The notes on prints, on the other hand, only mention artists' names, which are in principle arranged alphabetically by first name, and are clearly unfinished. Cartwright seems to have worked on it at various times, to the extent that he could no longer insert new entries in their proper places in the alphabet, but had to resort to a second and sometimes even a third column, to be been inserted later alphabetically. In any case, these notes about prints were considered important enough to paste them in the same album as the inventory of the paintings. The latter was probably a description of how the paintings were hung in Cartwright's house, although no names of rooms in the house are mentioned. Although it is possible that the lists of names and monograms are part of Cartwright's stocktaking as a bookseller, it seems more likely that the notes on prints are an index in the making (references to page numbers are missing), but what is this an index of?

These pages have so far been regarded by scholars as simply a list of names of famous artists noted by Cartwright that he might have liked to see represented in his collection of paintings.4 The list is somewhat confusing: it is headed ‘Italian masters’, but includes artists of other schools as well: Dutch (for instance Rembrandt, 1606/7-1669), Flemish (David Teniers II, 1610-1690), French (Nicolas Poussin, 1594-1665), German (Adam Elsheimer, 1578-1610) and Swiss (Hans Holbein II, 1497/98-1543). Perhaps for Cartwright ‘Italian masters’ was synonymous with artists from the Continent, or non-British?

The question then arises: where could Cartwright have read these names? What books on art did a Londoner have at his disposal in the second half of the 17th century? It soon became clear that these names, often Latinised, could not have been found in 16th- and 17th-century books on Italian (or Dutch) art in the particular spelling in which he wrote them. But this manner of writing them does appear in inscriptions on prints. It is also clear that Cartwright only partially understood what he was copying: he gave his list the title ‘Italian masters’, but it also includes publishers (indicated with ‘for’ or ‘form’) whose contribution was merely possession of the copperplate from which the print was made. Judging from the prints by the listed artists, Cartwright knew what pinx(it), delini(avit), f(ecit) and invent(it) meant, as he never includes those words. But he probably did not know what ‘for’ or ‘form’ meant.

Cartwright noted 168 names, listed in alphabetical order by the forename – 161 of them on the first four pages and 7 on the fifth page. As much as 35 of these are double entries, which means that there are only 134 artists, of which 22 could not be identified: 112 names, of which 31 are Northern or Southern Netherlandish. It is may be understandable that Cartwright used the title 'Italian masters' for his notes, because Italians are by far the majority:

8

Cartwright's Notes on Prints, p. 5, Dulwich College Archive, MS XIV, fol. 13 recto

9

Cartwright's Paintings Inventory, p. 1, Dulwich College Archive, MS XIV, fol. 1 recto

- 71 Italian artists (51 from the 16th century, 16 from the 17th century, and 4 from the 15th century)

- 19 Southern Netherlandish (14 from the 16th century, and 5 from the 17th century)

- 12 Northern Netherlandish (6 from the 16th century, 5 from the 17th century, and 1 unknown)

- 6 German (4 from the 16th century, and 2 from the 17th century)

- 4 French (1 from the 16th century, and 3 from the 17th century)

With the monograms on the fifth page, the emphasis shifts to German artists. There are 21 recognizable entries:

- 8 German printmakers (4 from the 16th century, and 4 from the 15th century)

- 6 Italian (5 from the 16th century, and 1 from the 17th century)

- 3 Northern Netherlandish (2 from the 16th century, and 1 from the 17th century)

- 3 Southern Netherlandish (all three from the 16th century)

- 1 French (from the 16th century)

When we combine the information on the five pages and remove all duplications, we arrive at a total of 125 names, some of which were not those of the artist or printmaker but of the publisher (the ones where ‘for’ or ‘form’ is added):

- 75 Italian names

- 20 Southern Netherlandish

- 13 Northern Netherlandish

- 12 German

- 5 French

The long versions of the names of the artists that Cartwright often records (see Appendix 1) suggest that he transcribed the signatures on reproductive prints of major compositions by, for instance, Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1598-1657) [10] and Philips Wouwerman (1619-1668) [11], not the simpler signatures (often just initials) on prints with single figures, landscapes, and animals, designed by the artists themselves, as peintre-graveurs. And it seems that Cartwright was looking for the inventors of the compositions: their names are often what he notes, not those of the printmakers. The latter can be found in the list of monograms (Appendix 2).

When we look over the list of Italian names, most of the artists who are still considered important today are present, such as the 16th-century Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Marcantonio Raimondi who engraved many of Raphael's compositions, as well as Giorgione, Tintoretto, Titian, Veronese and the Bassani from the North, the Carracci from Bologna, Correggio from Parma, and the Zuccari; and from the 17th century, Domenichino, Guercino and Guido Reni. Italian artists are well represented: from the canonical masters of the 16th and 17th centuries only Caravaggio and Salvator Rosa seem to be missing. This is not the case for the Northern and Southern Netherlandish artists (see table 1 and table 2) [12-13]. The few names of 16th- and 17th-century Northern and Southern Netherlanders provide a very imperfect picture of the artists of those regions. For the French there are only five names from the 16th and 17th centuries: one publisher (Antonio Lafreri, 1512-1577), three engravers (Jacques Callot [1592-1635], Léon Davent [fl. 1540-1556] and Gabriel Perelle [1604-1677]), and one painter, Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665). Neither the painter and printmaker Claude Lorrain (1604-1682) or any of the typical French portrait engravers such as Robert Nanteuil (1623-1678) appear.

10

Bartholomeus Breenbergh

Joseph opens the storehouse and sells corn (Genesis 41:55-57)

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-BI-4847

11

Johannes Visscher after Philips Wouwerman published by Jan Kralinge

Army camp with horsemen and a marketeer near a tent, c. 1665-1675

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. D,8.50

12

Table 1

Northern Netherlandish names in Cartwright’s notes on prints

13

Table 2

Southern Netherlandish names in Cartwright’s notes on prints

If we focus on the 17th century in Flanders, some well-known names, such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), do not appear, nor does Jacques Jordaens (1593-1678). Two engravers after Rubens are on Cartwright's list – Paulus Pontius I (1603-1658) and Lucas Vorsterman I (1595/6-1674/5) – but another important engraver after Rubens, Schelte Adamsz. Bolswert (c. 1586-1659), for instance, is missing. Was Anthony van Dyck considered too English to come under the heading 'Italian masters'? Or would Cartwright's six albums of prints have included separate volumes devoted to Rubens and Van Dyck, or to English portraits?

From the Dutch 17th century, three landscape painters are mentioned with the long versions of their names: Nicolaes Berchem (1621/22-1683), Bartholomeus Breenbergh(1598-1657) and Philips Wouwerman (1619-1668), demonstrating an apparent preference for large compositions with many figures. However, names of landscape painters such as Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/29-1682) and Anthonie Waterloo (1609-1690) are missing, let alone that of Hercules Segers (1589-1633), a master who was mainly collected by print connoisseurs. Dutch interior or genre scenes are also not represented. With the inclusion of Rembrandt (1606/7-1669) and Jan Lievens (1607-1674), Northern printmakers of mythical and biblical scenes seem to predominate (as in the Italian section). Both these artists also made images of the lower classes or peasants, which in England were called 'Anticks and drolls' (that is, humorous scenes of such figures as beggars or dancing farmers). With prints by the Frenchman Jacques Callot (1592-1635) and the Flemish artists Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569), Adriaen Brouwer (1603/5-1638) and David Teniers II (1610-1690), this kind of subject matter is reasonably represented. In general, however, Cartwright's preference seems to be for makers of the highest genre in the hierarchy of genres: the historical. This is in contrast to his preferences as they appear from his inventory of paintings. There, portraits (54) are dominant and the related 'tronies' (11).5

In view of this information, it appears that the five pages of notes on prints might be an index to two of the six albums of prints that Cartwright owned: the page with the monograms indexing the album of his best prints (mainly early German prints, but also ones by Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533) and Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617) and the four pages indexing Italian masters to one album of Italian masters or historical scenes. The content of the other four albums could have been French masters, German masters, Netherlandish masters and British masters. Or might those albums have been filled more according to subject matter – such as portraits, landscapes, seascapes, ‘Anticks and drolls’, or the topography of London, the subjects we see represented in Cartwright’s painting collection? Many portrait engravings were being made in London at the time, often using the new mezzotint technique (as explained in John Evelyn’s Sculptura of 1662), and foreign artists then working in London such as Marcellus Laroon I (c. 1648/9-1702) and Wenzel Hollar (1607-1677) were busy producing prints. It is probable that Cartwright also owned prints by them, or at least that he traded in them.

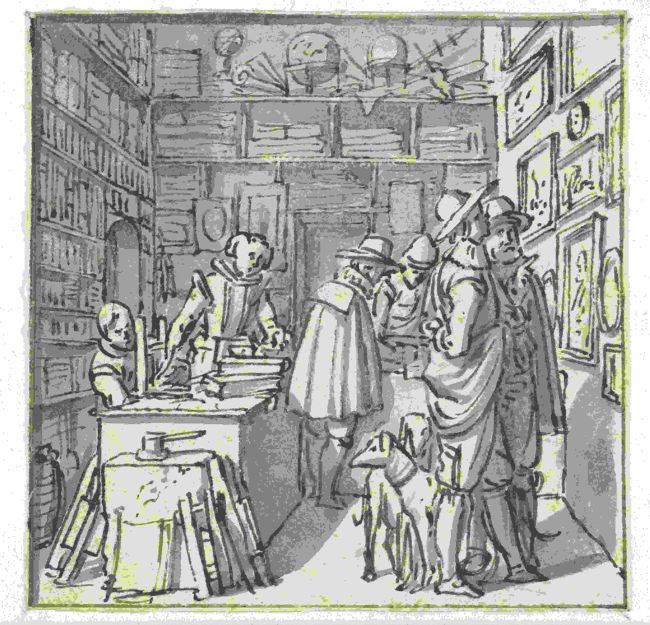

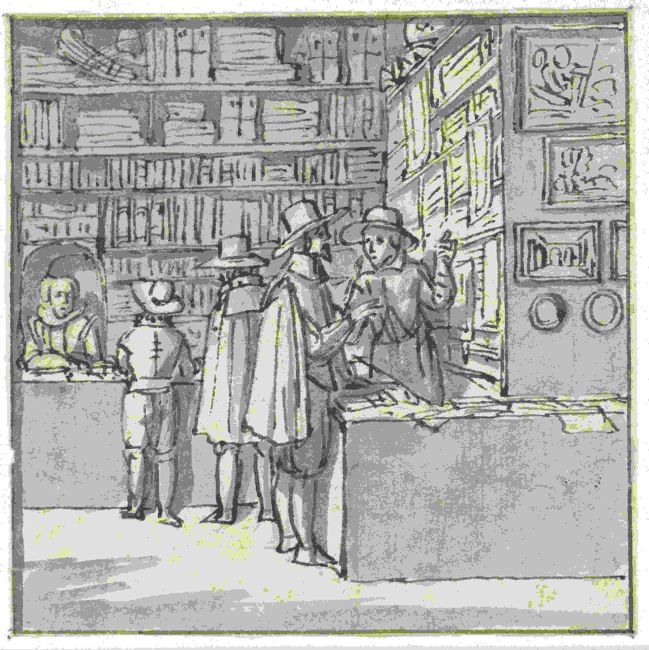

We do not know how his other four albums of prints were organized,6 just as we do not know how his bookstore functioned – or, indeed, whether he really dealt in prints. It was not unusual for a bookseller in the 17th century to do so, judging from the two drawings that Salomon de Bray (1597-1664) made in the 1620s of a bookshop, probably in Haarlem, where paintings, prints and/or drawings hang on the wall and there are two globes on a shelf [14-15].7

14

attributed to Salomon de Bray

Interior of a book and art store (with dogs), c. 1620-c. 1640

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1884-A-290

15

attributed to Salomon de Bray

Interior of a book and art store, c. 1620-c. 1640

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1884-A-291

At least two other lists of European artists’ names are known from the second half of the 17th century.8 One is handwritten by a South German Benedictine monk, Gabriel Bucelinus (1599-1681); the other, by an unnamed author, was printed in The Hague in 1671. Bucelinus was a scholar associated with the Weingarten Monastery in Baden-Württemberg and a collector of paintings. Bucelinus’ list has the title Pictorum Europae Praecipuorum Nomina (Names of the most distinguished European painters), contains 165 names and was made around 1664 [16].9 As with Cartwright’s list, there are duplications, and names that cannot be identified. There seems to be no particular logic to the order in which Bucelinus arranged the names. There are 60 Netherlandish artists, 50 Italian, 30 Central European, 2 French and 1 Spanish. The rest cannot be identified. The spelling of the names is sometimes curious – for instance ‘Boussin’ instead of ‘Poussin’ – suggesting that Bucelinus received information orally, perhaps from the Dutch painter Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-1678) or the German artist Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688), who he knew personally. They might have told Bucelinus of the reputation of Rembrandt, the only artist to whose name he added an appreciative remark: Rimprant, nostrae aetatis miraculum (Rembrandt, the miracle of our age).10 Hoogstraten was a student of Rembrandt while Joachim von Sandrart was in Amsterdam from 1637 until 1645, when Rembrandt was at the height of his fame (The Night Watch dates from 1642). Bucelinus travelled a good deal, including to Vienna and Venice, and he must have known many of the 165 artists listed, or at least encountered their works.

When we compare the lists of Cartwright and Bucelinus, 37 names are the same.11 We can regard them as the canonical artists of the second half of the 17th century. Of these 37 names, 11 came from the Northern and Southern Netherlands: Abraham Bloemaert, Pieter Bruegel I, Frans Floris, Hendrick Goltzius, Lambert Lombard, Lucas van Leyden, Karel van Mander, Rembrandt, Aegidius Sadeler, Bartholomeus Spranger, and Peter de Witte/Candido.

There are quite a few printmakers among them, or artists whose inventions were reproduced in print either by themselves or by others: it was considerably easier to become known through prints in Europe in the 17th century than through paintings alone. The names also include a writer about art, the artist and biographer Karel van Mander (1548-1606); writing books helped to acquire canonical status. It is remarkable that very well-known masters are missing from both lists, such as Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, although their work had been widely reproduced in print. Van Dyck is well represented in Cartwright’s album of drawings.12

While Bucelinus, in spite of his Latin-titled list and his scientific training, did not proceed in a traditionally scientific way, using written sources, that is exactly what the maker of the second list did, notes and all. It is entitled Tweederley Naem-lyst der Italiaensche Constenaars (Twofold list of Italian artists’ names), and was printed in The Hague in 1671 [17].13 Only one copy is known, which is kept in the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. It records hundreds of Italian artists as well as a number of Northerners who worked in Italy. Unlike Cartwright or Bucelinus, the anonymous author did make use of existing, mostly Italian, publications, which are mentioned faithfully in all his entries. Names without listed source, the author states, were recorded from drawings or prints. The first of the twofold list is arranged chronologically by year of birth, from 1154 to 1650 (p. 3-14) [18], and the second alphabetically in principle by first name, but with many cross-references between first and last names and nicknames (p. 15-36) [19]. There would not have been many intellectuals in The Hague who were proficient in Italian, had months spare to make an inventory of Italian artists’ names in a Lugt-like manner, and had the money to have their findings published. Could it have been a member of the Huygens family, or Jan de Bisschop (1628-1671)?

The anonymous author mentions ten publications, of which he considers five to be the most important, in this order:14 Vasari (1648 edition), Ridolfi (1648), Baglione (1649), Van Mander (1604), and De Marolles (1666) [20].15

In the Tweederley Naem-lyst der Italiaensche Constenaars three artists are mentioned who also appear in Cartwright’s list of ‘Italian masters’: Strada or Jan van der Straet/Stradanus (1523-1605), Lamberto Suave or Lambert Suavius (c. 1510-1567), and Pietro Candido or Peter de Witte (c. 1548-1628). A print by Cornelio or Cornelis Cort (1533?-1578), who is also mentioned in the Tweederley Naem-lyst, served as a model for one of the works in Cartwright’s album of drawings [50-51]. The Hague lists, based mainly on Italian sources, also mention the Northerners Lodovico Pozzo Serrato or Lodewijk Toeput (c. 1550-1604/5), Henrico Valckenburg,16 and Martino or Maerten de Vos (1532-1603). These last three, however, do not appear in the lists of Bucelinus or Cartwright.17

Cartwright, Bucelinus, and the anonymous author from The Hague were all concerned with artists from foreign countries and not with artists from their own city or country. Until then it had been usual to focus on the artists from one's own city or country when writing about art. Was it the internationalization of the art trade, or at least of the print trade, that led to a resident of London, a monk from southern Germany and a resident of The Hague all showing an interest in art from beyond their own borders?

The fifth page of Cartwright’s notes on prints includes a list of 28 monograms that he had found on his best prints. He notes three monograms more than once – those of (Hans) Sebald Beham (c. 1500-1550) (3 x), Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617) (2 x) and Georg Pencz (1500/1502-1550) (3 x) – and his list actually features only 23 different artists. Of these 23 artists’ monograms, 8 are German; 6 Italian; 6 Northern or Southern Netherlandish, of which 4 were already in the list with Italian Masters (Appendix 1);18 1 French; and 2 that could not be identified. It is striking that the majority of the artists lived in the 16th century. Only 2 are 17th-century – Carlo Ridolfi (1594-1658) and Jan Lievens. The 4 who lived in the 15th century were all Germans: Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Master MZ (fl. c. 1500), Israhel van Meckenem (c. 1440/45-1503) and Martin Schongauer (1430/50-1491).

Throughout the 17th century, all over Europe, we can see print collectors and print sellers making lists like these in order to map their holdings. It was not until 1699, 13 years after Cartwright’s death, that the first publication on monograms, to identify the artists hiding behind those enigmatic initials, would appear. This first reference work was Cabinet des singularitez d’architecture, peinture, sculpture et graveure; ou, introduction à la connoissance des plus beaux arts (1699-1700), published by the Parisian artist and print dealer Florent le Comte (c. 1655-c. 1712).19

I will discuss two earlier lists of monograms, not because Cartwright knew them but to show what was known about artists’ monograms elsewhere in Europe in the 17th century. The first is the inventory of the Amsterdam estate of the painter and art dealer Jan Bassé (1572-1636),20 dated 6 January 1637, and the second is the publication by Michel de Marolles of 1672.

The possessions of Jan Bassé were auctioned from 9 to 30 March 1637. The auction has attracted the attention of several Rembrandt scholars, since many prints by Rembrandt were offered in it, and Rembrandt himself was a buyer at the sale. The inventory of Bassé’s estate had been drawn up two months before the auction. It was partly published in Strauss and Van der Meulen’s book of Rembrandt documents of 1979 [21].21

It is striking that in Bassé’s inventory we see some of the same monograms that were later recorded by Cartwright: those of Heinrich Aldegrever, (Hans) Sebald Beham, Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden and Georg Pencz. But the Amsterdam compilers of that inventory, no doubt aided by information from the deceased himself, knew, fifty years before Cartwright, which artists were hiding behind these monograms, whereas Cartwright seems to have been in the dark.22

The Parisian collector Michel de Marolles (1600-1681), who twice assembled collections of more than 100,000 prints, can be regarded as a connoisseur. He published a catalogue of his first collection in 1666.23 After he had sold that to the French King Louis XIV (1638-1715) in 1667, he built up a new collection, of which he published a catalogue in 1672 in which he also noted monograms.24 This publication is disappointing. While De Marolles included images of monograms and listed a whole series of artist’s names in his text, he did not link images with texts: that was left to the reader. If Cartwright had known the publication, it would not have helped him much in deciphering the monograms on his ‘best prints’.

16

Bucelinus’s list of artists’ names

17

Title page of the 1671 lists

18

Beginning of the chronological list

19

Beginning of the alphabetical list

20

List of publications used in the 1671 lists

21

Strauss/Van der Meulen 1979, p. 142

Notes

1 Published in Kalinsky/Waterfield 1987, p. 20–27.

2 Dulwich College Archive, MS XIV, fol. 11r-13r.

3 A page with entries 186 to 209 is missing, so 215 entries of paintings remain. Cartwright did not give a value for 23 of these 215 entries.

4 Kalinsky/Waterfield 1987, p. 9, talking about this list with ‘names of the great artists of his time and of the previous century’, say ‘Doubtless Cartwright lacked the financial resources to make a collection of major foreign masters’.

5 Among the 215 (see note 3 above) entries of the paintings inventory we also find animals (13) and still lifes (16), biblical (25) and mythological (11) subjects, landscapes (20), seascapes (18), interiors (25), indeterminate (16), and the special section 'anamorphoses' (7).

6 Other possibilities include arrangement by theme. Rather than by genre it might have been according to books of the Bible: e.g. the Old Testament, New Testament, and lives of the saints; or geographically, by continent, country and city; or historically, by country and within that chronologically by monarch; or alphabetically, according to the person portrayed.

7 For the attribution to Salomon de Bray: Heijbroek 1984-1985.

8 Both lists were brought to my attention by Marten Jan Bok, for which many thanks. Of course there are many more lists of artists' names from that time, but these usually concern artists from the collector’s own city or country. The Amsterdam doctor Jan Sysmus concentrated in his register of painters (c. 1669-78) on Dutch contemporary (living) artists, as did Arnout van Buchel (1565-1641) and Johannes de Witt (c. 1565-1622): Van de Wetering 1997, p. 60. Constantijn Huygens II (1628-1697) would also have compiled a list of Italian painters. Could it be the list printed in The Hague? According to Dekker, Huygens had written an encyclopaedia that does not survive: Dekker 2013, p. 68.

9 Schillemans 1987, where Bucelinus’s list is transcribed and annotated.

10 Van de Wetering 1997. This publication is devoted mainly to Rembrandt’s fame in later times.

11 In alphabetical order, they are: Hans van Aachen, Federico Barocci, (Jacopo) Bassano, Abraham Bloemaert, Paris Bordone, Pieter Bruegel, (Agostino, Annibale, Antonio or Lodovico) Carracci, Correggio, Albrecht Dürer (in Cartwright’s list of monograms), Frans Floris, Giorgione, Hendrick Goltzius (in Cartwright’s list of monograms), Hans Holbein, Giovanni Lanfranco, Leonardo da Vinci, Lambert Lombard, Lucas van Leyden, Karel van Mander, Jacopo Palma Giovane or Jacopo Palma Vecchio, Parmigianino, Georg Pencz (in Cartwright’s list of monograms), Pordenone, Nicolas Poussin, Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Raphael, Rembrandt, Guido Reni, Giulio Romano, Hans Rottenhammer, Aegidius Sadeler, Joachim von Sandrart, Andrea del Sarto, Bartholomeus Spranger, Tintoretto, Titian, Paolo Veronese, and Peter de Witte/Candido.

12 In the album related to Van Dyck are: (1) The right arm of Margaret Lemon, https://rkd.nl/en/images/310141 (after https://rkd.nl/en/images/226785); (2) King Charles I, https://rkd.nl/en/images/310344 (after https://rkd.nl/en/images/310177 ); (3) Lucas Vorsterman, https://rkd.nl/en/images/309980 (after https://rkd.nl/en/images/241393 ); (4) Lady Frances Cranfield, Lady Buckhurst, later Countess of Dorset (1622(?)-1687), copy (in reverse), https://rkd.nl/en/images/310363 (after https://rkd.nl/en/images/236659 ); (5) Portrait of a woman, https://rkd.nl/en/images/310183 (after https://rkd.nl/en/images/310173); (6) Head and arm, of Algernon Percy, 10th Earl of Northumberland, https://rkd.nl/en/images/310364 (after https://rkd.nl/en/images/58127 ).

13 On the title page the ‘7’ is changed to ‘8’ in ink, making the date 1681. It is not known who did that or when. I think it makes more sense to stick to the printed year of publication, 1671.

14 ‘Maer zijn de drie of vier eerste de voornaemste, als mede de tiende’.

15 Vasari 1648 is probably Vasari/Manolessi 1648-1663; Ridolfi 1648; Baglione 1649 (2nd edn.); Van Mander 1604; De Marolles 1666.

16 This artist does not appear in modern handbooks. He is only recorded in Ridolfi 1648, pt. 2, p. 226: ‘Henrico Valchemburch Augustano Discipolo dell’Aliense, apprende la maniera di Venetia. Ritorno alla Patria’. Two paintings are mentioned: una bellissima ignuda Galatea (p. 195), and Diana al bagno con Calisto scoperta grauida (p. 219).

17 There are also several artists signalled as ‘Fiam[m]ingo’ or ‘Tedesco’, but with only a first name they are difficult to identify.

18 They were Lucas van Leyden, Jan Lievens, Lambert Suavius and Hans Sadeler. New Netherlandish names on this page are Cornelis Bos and Hendrick Goltzius.

19 Many thanks to Yvonne Bleyerveld, email, 25 October 2022. On Le Comte and his book, Meyer 2018.

20 On Bassé: Van der Veen 1992A, p. 314; Robinson 1981, p. xxxiv.

21 Strauss/Van der Meulen 1979, p. 142.

22 That Beham also appeared as ‘Subbelbyn’ in Bassé’s inventory seems apocryphal; the other monograms were provided with the correct names.

23 De Marolles 1666.

24 De Marolles 1672.